| « Back to article | Print this article |

'One day, someday, when all this is over and those who survive to tell the tale to our grandchildren, the corona pandemic of 2020 will join cataclysms such as killer floods, communal bloodbaths, or a mass migration rising to Partition levels,' observes Sunil Sethi.

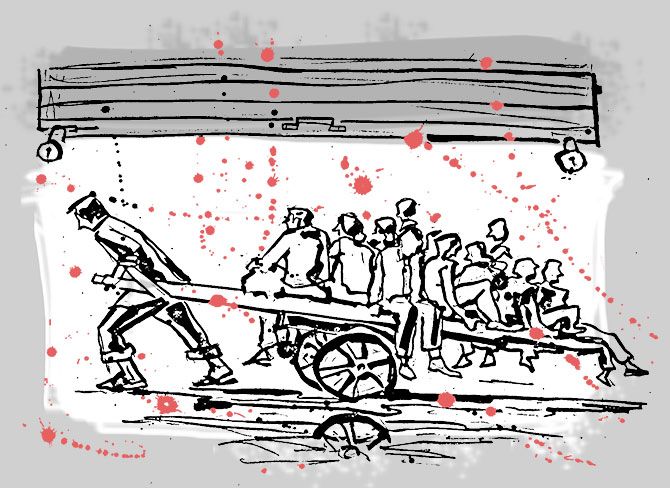

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

As the first stirrings of life return to the streets, there is something hesitant, almost furtive, about the slow lifting of the lockdown.

Cars are now visible from my window on an empty thoroughfare and -- my heart jumped at the sight -- even a bus or two.

The popular bakery down the lane is open for business but you cannot enter: Like children, noses pressed to the glass questing for forbidden morsels, you point to a preferred loaf of bread -- though there isn't much choice.

The chemist has resumed home deliveries but the stationer has pasted a notice announcing a three-day working week.

In neighbourhoods like mine, all entrances and exits are shut, bar one that is monitored 24x7; the nearby basti, too, is practising a shutdown in its lanes: No thelas or vehicles allowed.

I asked our garage mechanic how his children, who attend the municipal school, were managing lessons.

"They were sent lockdown homework on my mobile and told to prepare." He broke into a grin before adding, "Prepare for exams, which may happen one day or never happen."

One day, someday, when all this is over and those who survive to tell the tale to our grandchildren, the corona pandemic of 2020 will join cataclysms such as killer floods, communal bloodbaths, or a mass migration rising to Partition levels.

As of this week, the country has crossed the 330,000 mark in infections.

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal says the city's hospitals are ready for an influx of COVID-19 patients, but medical practitioners such as Dr Ambarish Satwick, a vascular and endovascular surgeon at the Sir Gangaram Hospital, is among those to rip into the government's notions of prepared medical capacity or strategy.

Dr Satwick's blunt but lucid arguments were initially aired on a WhatsApp neighbourhood group but, as a cautionary account, they have gone viral (to use that painful phrase).

His prediction is that the epidemic is just about taking off in Delhi. 'At some point in early July (if not earlier), we're likely to observe a complete breakdown of our healthcare infrastructure, which means that hospitals in the NCR will run out of beds to treat Covid patients...'

Easing the lockdown means 'your chance of getting infected today is 15 times more than what it was in the beginning of May. It will be a hundred times more by June-end. And there could be a second surge by September.

Given the unpredictability of the virus, the plethora of statistics (floating like a parallel contagion) is fundamentally a form of roulette.

Dr Satwick told me: "Mr Kejriwal's reservation of a percentage of beds in private hospitals is like a fatwa. A dedicated Covid hospital has to be fitted out distinctly from one for non-Covid patients."

This is true as patients with other medical conditions have complained of being sidelined in the corona emergency.

And there are certain conditions, such as women in labour, that cannot wait, says Dr Satwick, whose wife is a pediatrician: "What do you do about those?"

My own need was minor, a dental problem that persisted through the lockdown. Relieved that the father-son practice I have patronised for 30 years had reopened, I entered another kind of clinic.

The usually busy waiting-room was empty, disinfecting and PPE protocols were rigorously in force.

Strips of blue barrier tape were stuck on door handles and armrests of dental chairs.

"Don't forget we are dealing with saliva and blood in highly sensitive and contaminable areas. We can't be careful enough," young Dr Srijan Mehta explained.

He has pared down his schedule to take only crucial cases due to curtailed staff and other restrictions.

The weeks of incarceration have ineluctably changed all lives, and I asked Dr Mehta how they had changed him. He had become more philosophical and tried to reorder life to basic essentials.

Friends and colleagues similarly speak of reappraising priorities and editing routines if they are fortunate enough to work from home.

For some expenditure is cut down (on clothes, transport, and going out) and time, having acquired an elastic dimension, is available for reading, reflecting, or spending with loved ones. Simplification, is the word often used.

Anachronistically, however, for many the exigencies of the lockdown have complicated lives.

It has demolished taken-for-granted support systems and magnified uncertainties.

Professionals unable to WFH, or with small children, or shorn of domestic help and endangered jobs, the worries have only begun.

The worst-off are the multitudes, outside the safety net of the soldiering middle classes, that face interminable displacement and destitution.

But the biggest contradiction of the coronavirus contagion is that it is both leveller and divider.

As an affliction, it brooks no difference between divisions of region, class, rich, or poor.

And yet it drives the wedge deeper between those with the wherewithal to ride it out and those on the margins unable to withstand its assault.

Production: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com