| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Coalition governments, sometimes assumed to mean years of political instability, actually saw key institutions emerging with greater strength -- the Election Commission, the judiciary, the press, and civil society at large, among others.'

'The question now is whether the clock is being turned back in a new political phase,' asks T N Ninan.

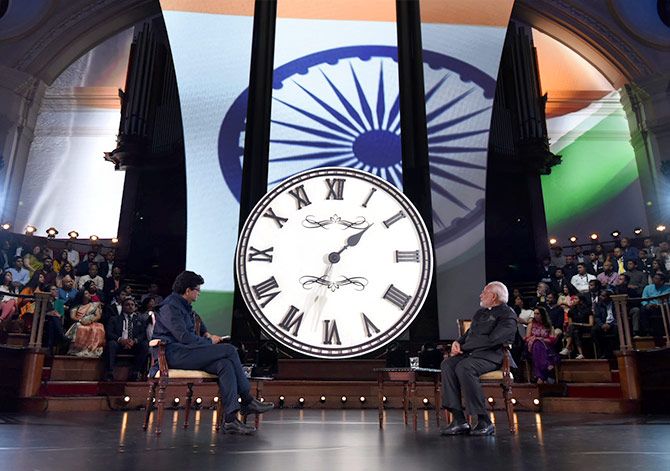

IMAGE: Prime Minister Narendra D Modi at the Bharat Ki Baat event in London, April 18, 2018. Photograph: Press Information Bureau

If one surveys the institutional scene, there is the complete waste of half the Budget session -- reducing the Lok Sabha to the semi-relevance to which many assemblies have already been reduced; so much so that even a no-confidence motion could not be taken up for discussion and voting.

One might add that the BJP protests too loudly that the Opposition is to blame.

Consider then the virtually open revolt that is evident in the Supreme Court, with some of the senior-most judges continuing to air publicly, and in the strongest possible language, their concern about the state of affairs in the Court -- and their fear that (not to put too fine a point on it) the government is trying to pack the Court.

One must consider the state of law and order in what is arguably the country's most important state.

A chief minister with criminal cases against him and a history of leading a vigilante group has presided over his government withdrawing charges against him, promoted vigilante groups, asked the police to control crime by stepping completely outside the framework of law, proposed that the state withdraw cases against selected politicians (you can guess their colour) and not taken the obvious action mandated by law when a party legislator is accused of raping a minor.

Finally, one has to consider the decay of social capital and the lack of mutual trust when claims by constituent states of the Union increase in stridency, when needless actions cause communal tension and violence in parts of the northern heartland, when the country's largest minority feels under majoritarian siege, when political parties in West Bengal, Kerala and elsewhere resort to open violence to settle issues, when the Opposition starts distrusting the Election Commission, and when the coming election season is viewed by many with a sense of dread.

A well-ordered society that hopes to do well economically and by its citizens has to strengthen its foundational institutions (Parliament, the judiciary, the larger justice system, and the administration).

It has to ensure that the machinery for law and order and for tax collection functions under proper oversight, that due process is not cast aside as expendable, that the electoral process is fair, and that fundamental rights are in fact available to citizens.

Many of these institutions and rights were under siege during the years of a single person's political dominance slightly more than four decades ago.

The subsequent years of coalition or minority governments, sometimes assumed to mean years of political instability, actually saw key institutions emerging with greater strength -- the Election Commission, the judiciary, the press, and civil society at large, among others.

The question now is whether the clock is being turned back in a new political phase.

Thirty-eight years ago, all of India was in a state of shock when it was reported that the police in Bhagalpur had resorted to blinding petty criminals.

Today policemen are simply killing those considered to be criminals; let alone shock, the campaign is said to enjoy public support.

This has been explained as an understandable reaction to years of lawlessness that went before, but society enters a dangerous phase when foundational principles and institutions are seen as mere tactical assets, to be set aside when convenient.

Especially when strongman rule and sectarian nationalism have gained new currency in many countries, the importance of social and institutional capital cannot be over-emphasised.