| « Back to article | Print this article |

This is one of those crises where it does not only matter that you do something, but how you do it, notes Mihir S Sharma.

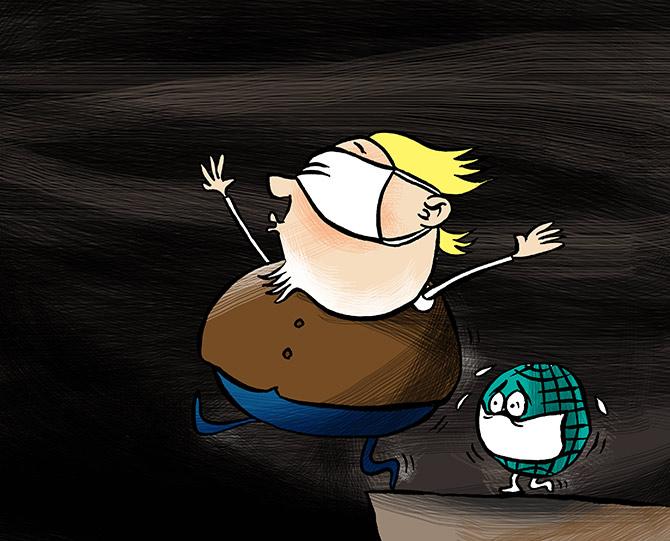

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

What sort of leadership appears to be working during this pandemic?

On some level, any form of leadership at all -- it is a well-known effect of national crises that there is a surge in support for whoever appears to be in charge.

The 'rally round the flag' effect, however, is often temporary.

For example, President Donald J Trump's approval rating going into the US's battle against the coronavirus, in early March, was negative 10 points -- in other words, the percentage of respondents who on average disapproved of his performance was 10 percentage points higher than those who approved.

In end March, he had a small bump: It went up to negative four points.

But now it's back down to early March levels.

Perhaps, therefore, this is one of those crises where it does not only matter that you do something, but how you do it.

Even leaders who have effortlessly sailed through previous threats to their popularity are struggling with this one.

Consider the original archetype of the macho nationalist strongman, President Vladimir Putin.

The Russian leader is still remarkably popular -- his approval rating is around 60 per cent, or perhaps just below that.

But amid a pandemic that has taken root in a Russia with health care facilities that do not match its superpower pretensions, his popularity has in fact suffered -- this is the lowest number he has achieved since he took power in 1999.

The last time his polls approached such numbers was in 2013. (That's about when Russia invaded and annexed Crimea, sending its president's popularity soaring again. Perhaps its neighbours should be worried about more than the spread of the coronavirus.)

Putin -- normally the most confident and visible of leaders -- has been so low-profile during this crisis that his spokesman actually had to clarify that 'the president is not in a bunker'.

The fact is that, if there was a clear route to turn such a pandemic to political advantage, Putin would have been the first to find it. (He still may.)

Populist strongmen around the world have usually used the occasion to further their own agendas or consolidate their own powers.

Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines shut down an independent media house.

Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil -- who calls the coronavirus 'the little flu' -- refuses to wear a mask, famously coughed into a crowd of his anti-lockdown supporters, and has attacked his country's governors for their pandemic control plans.

And it's not just the right-wingers -- Mexico's left-wing president hasn't covered himself with glory in this period either.

And that's just in democracies.

Viktor Orban of Hungary has used the pandemic to amass so many emergency powers that, according to the raters at Freedom House, his country should no longer count as a democracy.

One would like to believe that, in a situation like this one where actual ability and trust in others -- medical doctors, epidemiologists, supply chain experts, and so on -- matters, the sort of fly-by-the-seat-of-their-pants populists who have dominated politics in recent years will come to grief.

You might point to the careful, data- and expertise-driven leadership of Germany's Angela Merkel (who famously has a PhD in quantum chemistry) or of Taiwan's Tsai Ing-Wen (whose vice-president, incredibly, happens to be a Johns Hopkins-trained epidemiologist).

Surely voters will recognise the obvious superiority of this approach?

I wouldn't be too sure.

Both Merkel and Tsai have won praise for deferring to science in their approach to the virus, and for seeking to be transparent about how policymaking in a time of unprecedented uncertainty should work.

Even aspirants to power have sought to associate themselves with such an approach: Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has a public health advisory committee that he has said drafted his approach, and Rahul Gandhi has held two recorded question-and-answer sessions with well-known economists on how to address the costs of and recovery from India's lockdown.

Yet the fact is that even then, people who should know better would like to mock such attempts at humility from politicians, in power and out.

Politicians should be humble about what they know, and even more about what they don't know.

In a situation like the coronavirus, the fact is even those who have studied epidemics, respiratory diseases, virus transmissions, or sudden supply shocks do not know as much as we would like.

Yet they are learning all the time, and remain the best positioned to make it clear to both policymakers and the public what the best path ahead is.

Political leaders should make it clear that they are deferring to those who have some expertise; and the experts should make it clear how they are informing themselves and updating their prior beliefs.

The notion that leadership is all about communicating confidence -- even when there are no rational grounds for confidence -- is precisely the sort of small-minded, over-simplified, short-sighted and plain wrong mantra that sends the world into this populist death spiral.