| « Back to article | Print this article |

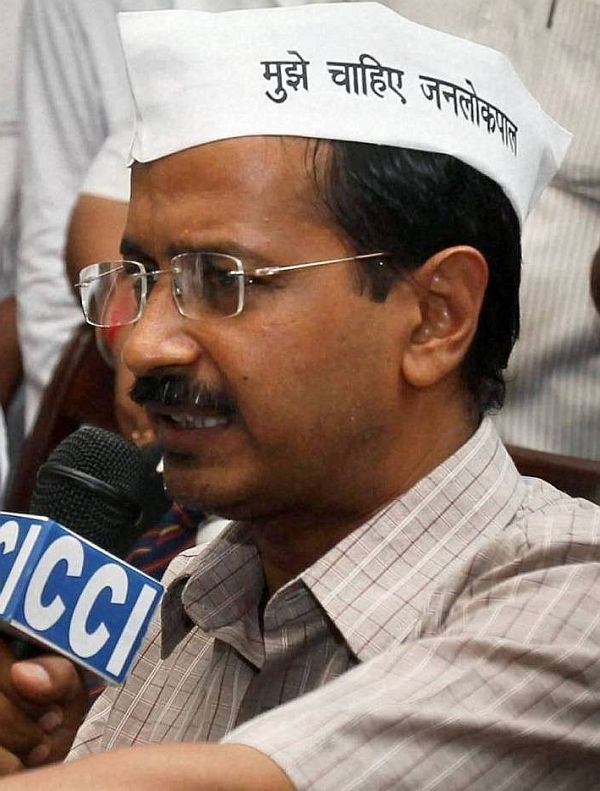

Arvind Kejriwal’s every posture and mudra is carefully choreographed to resemble those of the original Mahatma, but the vision is stunted, the hidden agendas often leak out, says Dr Anirban Ganguly.

Arvind Kejriwal’s every posture and mudra is carefully choreographed to resemble those of the original Mahatma, but the vision is stunted, the hidden agendas often leak out, says Dr Anirban Ganguly.

Arvind Kejriwal’s actual political raison d’etre is finally out. His sole driving objective, as dictated by the forces he and his political conglomerate represent, is to prevent Narendra Modi from pulling through to lead a stable formation which shall ultimately provide India with the much needed governance with a vision. The self-confessed ‘anarchist’ with an enforced Gandhian hue is out to fulfill his agenda of injecting the seeds of anarchism into the various systems of this land.

Kejriwal’s every posture and mudra is carefully choreographed to resemble those of the original Mahatma, but the vision is stunted, the hidden agendas often leak out and the fact that the attempt at resemblance is a forced and a fake one is gradually becoming evident, at least to those with a genuine understanding of Indian politics and of the role of imposters and pretenders in it.

It would be interesting to take a look at some of the Mahatma’s positions and to see how they contrast with the self-styled pocket mahatma of present day Indian politics.

In sharp contrast to the image of the present day anarchist, the Mahatma was for evolving systems. In support of his position that these systems were to be carefully crafted and framed to suit the Indian temperament and ethos the Mahatma did not call for anarchism but worked and experimented to evolve newer frameworks. His experiment to evolve a Constitution for India in collaboration with the Raja of Aundh is a forgotten episode in Indian political history. Far from calling for the overthrow of the Constitution or of those manning it, Gandhi himself worked out the details of a Constitution which would be responsive to the people and enlist their cooperation as well as the cooperation of the ruler in manning the machinery of the state.

A princely state comprising of 72 odd villages scattered over the districts of Satara and Sangli in Maharashtra and Bijapur in Karnataka Aundh became for a decade or so the field of experiment for a truly responsive and cooperative democracy. Gandhi himself drafted the Constitution in collaboration with Swami Bharatananda, a Pole-turned-Hindu, and meticulously followed its implementation. Section 24 of the ‘Aundh State Constitution Act of 1939’ clearly laid down that ‘Shriman Rajasaheb is the first servant and the bearer of conscience of the people of Aundh’ and the last para of the proclamation, set the ethical and moral dimension when it declared that ‘self-government implies self-control and self-sacrifice.’

The venerable Raja, a keen enthusiast in the experiment, gladly made the declaration and along with his heir consented of his free will to be part of the experiment. Absent was any kind of coercion, non-cooperatism or any legitimising of anarchy. In fact around this time, writing in his Harijan, the Mahatma had observed on the question of the demand for a constituent assembly, that the ‘way to democratic Swaraj lies only through a properly constituted assembly, call it by whatever name you like’, absent was any call for anarchic posturing.

In his approach to industrialists Gandhi was frank. He essentially saw them as partners and collaborators in the multi-dimensional expressions of his scheme of Swaraj. So frank was his approach that he could, while castigating them for their neglect of labour welfare, also appeal to them to be part of the movement for national reconstruction. The Mahatma then had no hidden quid pro quo with ‘capitalists’ as the present caricatured copy of his persona has.

Some of the Mahatma’s exchanges with one of his principal financiers, G D Birla, would be an interesting case in point. ‘My thirst for money’, wrote Gandhi to Birla sometime in 1927, ‘is simply unquenchable. I need at least 200,000 rupees for khadi, untouchability and education. The dairy work makes another 50,000. Then there is the ashram expenditure. No work remains unfinished for want of funds but God gives after several trials…You can give me as much as you like for whatever work you have faith in.’

Birla made a donation of Rs 78,000 in January 1928 writing that he left the matter entirely to the ‘discretion of Mahatmaji’ suggesting that ‘preference be given to such schemes as may bring Swaraj nearer…’

In a clear contrast to the present day advocates of Swaraj, Gandhi did not harangue on its necessity but rather approached the issue, in his own way, through the initiation of a number of schemes and organisations that would work to preserve and nurture indigenous systems of growth and development at the grassroots while bringing about a general awareness on the need for Swaraj. It was remarkable to see the large number of selfless volunteers that his projects for national reconstruction attracted and of how a silent and tireless cadre gradually emerged with the pledge of ushering in true Swaraj.

In his protests against the established system and its adverse effects on the Indian polity, in his resistance against a system which essentially failed to evaluate the Indian ethos, the Mahatma exuded a certain dignity of approach, a dignity which usually emerges from the certainty and conviction of one’s visions and formulation. There usually was no space in his scheme of things for rabble-rousers and peddlers of false hopes.

These were some of the ways and approach thus of the Mahatma, anarchism was surely not his way -- for him Swaraj was a constructive effort at envisaging and evolving indigenous alternatives, it did not involve condemning the other.

The anarchic path to a false Swaraj is the promise of fake Mahatmas; the sooner we internalise this truth the clearer our choices shall be!

Dr Anirban Ganguly is director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi.