| « Back to article | Print this article |

Attlee said Great Britain had concluded that the Indian element of the army was no longer reliable and that Netaji's Indian National Army had demonstrated that.

That had shaken the foundation on which Britain's Indian empire rested, argues Lieutenant General Ashok Joshi (retd).

The two English words that I first became aware of were 'war-time' and 'temporary'.

I could make some sense of them because war had entered our lives through shortages and non-availability of essentials.

Similarly, the freedom movement had filled the atmosphere because of processions of khadi clad men and women roaming the streets with the Congress flag.

One could not help being aware of World War II and the freedom movement. They were intertwined.

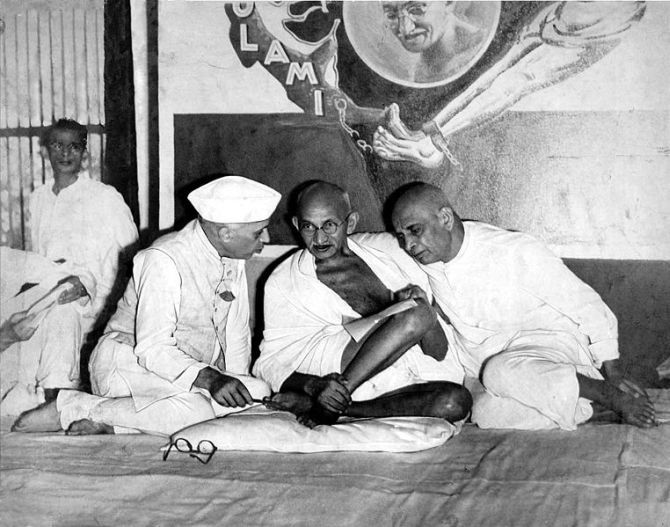

Let me begin with an anecdote. During the Congress' Nagpur session in 1925, Jinnah during his introductory remarks referred to Gandhi as Mr Gandhi.

That was interpreted by the crowd as a deliberate offence to the Mahatma. Jinnah was heckled and not allowed to speak.

Those on the stage did not ask the crowd not to misbehave. That day Jinnah decided that:

That incident ultimately brought about the conception and creation of Pakistan.

I do believe, like so many others, that there is the Law of Unintended Consequences: Actions of the powerful always have effects that are unanticipated or unintended.

You would recall that the cartridges smeared with animal fat extracted from pigs and cows that the East India Company's army introduced resulted in the 1857 Mutiny.

I would request you to keep this law in mind while arriving at your own conclusions with regard to the evolution of the freedom movement.

Everything did not happen as it was intended to by the leaders.

Before going any further, I wish to categorically state that I have the highest respect for all those who strove for freedom, as I ought to, and if I occasionally slip up, forgive me.

There were three streams of those who strove for Independence of India from British rule:

When the Mahatma came on the scene, initially, he was a follower of Ranade/Gokhale, but soon he introduced the idea that the means used to achieve independence were as important as the objective itself. Thereafter, the krantikaraks were treated as if they were beyond the pale.

All those who rose against the British in 1857 and later who used force against the British were ignored and their memories were deliberately wiped out. The last in the lot was Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

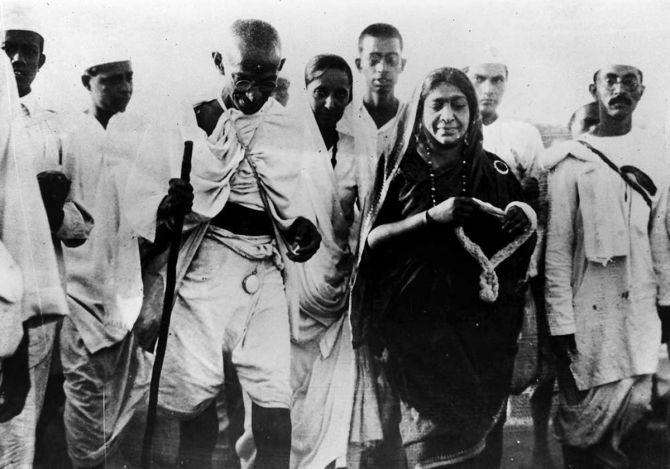

The Mahatma introduced the idea of Satyagraha which in effect meant that he appealed to the goodness of the rulers.

He said to them, 'Punish me, but I will not cooperate with you, I will not abide by your laws. You have no business to rule unjustly. I will submit to any punishment you inflict on me.'

Thus, he occupied the moral high ground.

Let us dwell a little on this approach: This was a very shrewd move to convert Indian weakness into strength.

India, as result of almost a millennium of slavery, had been left without a strategic culture.

Indians, generally, chose to be 'victims', rather than retaliate.

Indians were willing to suffer as victims, but not as fighters.

Under the Mahatma's leadership, many allowed the British to break their heads as Satyagrahis, instead of retaliating in any manner.

In short, it was possible to motivate an Indian to suffer pain and punishment without retaliation.

Soon after Tilak's death on August 1, 1920, the Mahatma took over the reins of the Congress.

He launched many movements, but as soon as there were instances of violence, he just terminated them. Often, that proved to be an anti-climax for the agitators.

Under his leadership the Congress, and the freedom movement, gathered momentum as never before.

When elections were held under the Government of India Act of 1935, not unexpectedly, the Congress formed governments in 8 provinces in 1937.

The Muslim League under Jinnah became an alliance partner in the then United Provinces. The League was only a junior partner.

This was a golden opportunity for the Congress to make up with Jinnah, but it squandered the opportunity.

War clouds were gathering and in September 1939 Great Britain declared war on Germany.

Soon after, Lord Linlithgow, the viceroy, without caring to consult the provincial governments, declared that India was also at war.

The Congress took offence, as they had a right to, but overplayed its hand thereafter and resigned in December 1939.

The Congress lost an opportunity to convince the Muslims that the Congress governments treated alike Indians of all religions, and that Hindus did not get any preferential treatment.

The Congress intention was only to jolt the viceroy by pointing out his serious error of judgement. But looking at the consequences one is reminded of the law of the unintended consequences.

Jinnah declared in December 1939 that day of resignation was 'deliverance day'.

He implied that the Congress during its rule had ill-treated Muslims, and that Muslims would only prosper in Muslim majority areas where the leadership was with the Muslims.

Muslims then formed nearly 13 percent of the population. They preferred British rule to Hindu dominated government. Many Muslims believed that the creation of a Muslim majority Pakistan was the only answer.

World War II raged fiercely and if there was anything that fully occupied the minds of British decision makers in England and in India, it was immediate survival, and subsequent revival.

India was the base from which the British had to fight the Japanese.

The Congress was willing to help the British provided it promised Independence in a time bound manner.

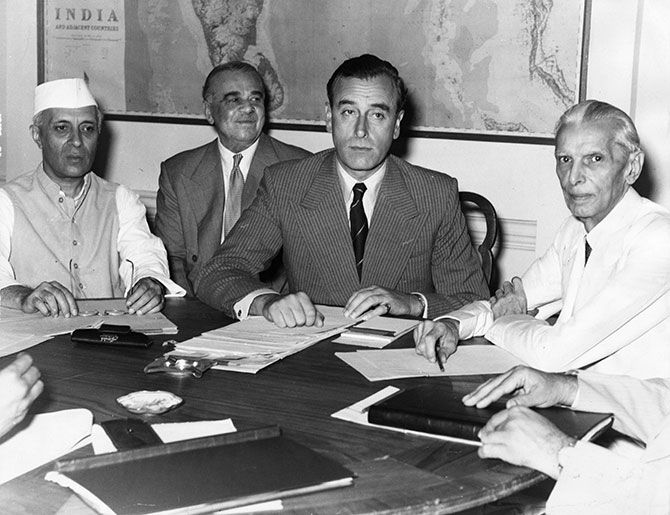

In March 1942, the Stafford Cripps Mission was sent to India to negotiate with the Congress. But the best that the British were willing to offer India was Dominion status. They were also unwilling to commit to any time frame.

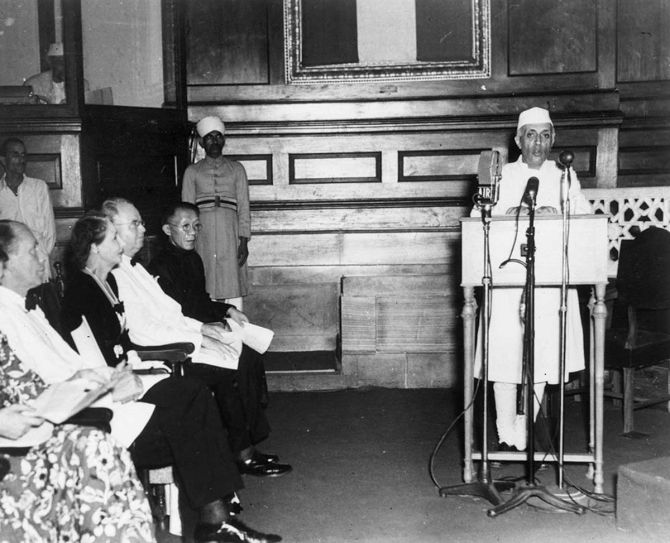

It was in these circumstances that the Congress decided to launch an agitation. The Congress working committee resolution was proposed on August 8, 1942 by the Mahatma himself.

He started off by emphasising that non-violence would remain the soul of the agitation, and to that end, he said the following: 'God has vouchsafed to me a priceless gift in the weapon of Ahimsa. I and my Ahimsa are on trial today.'

'If in the present crisis, when the earth is being scorched by the flames of Himsa and crying for deliverance, if I failed to make use of the God given talent, God will not forgive me and I shall be judged unworthy of the gift. I must act now. I may not hesitate and merely look on, when Russia and China are threatened."

The essence of the resolution was:

The short and imaginative title for the resolution was proposed by Yusuf Mehrally: 'Quit India'.

The Congress leadership was arrested during the following night. People took to streets, burnt railway stations, broke telegraph lines, took out processions.

Nearly 100,000 agitators were arrested. By November 1942 the agitation had lost its momentum, and the British were free to prepare for war in Burma.

A huge number of Indians were joining the army -- Hindus and Muslims both.

The British were appreciative of the supporting role that Jinnah played: The Muslim League under his leadership wholeheartedly supported the British war effort.

The British looked upon the Congress as a mainly Hindu organisation that created problems for the British whereas Muslims went out of their way to help the British in the hour of their need.

Provincial leaders of the Muslims in the Punjab and Bengal were not keen on Partition; they preferred to rule over undivided Punjab and undivided Bengal because that gave them political heft.

Jinnah had no problem with British rule. He wanted disproportionately larger representation for Muslims under British rule.

He put forward a strange theory in justification: Hindus and Muslims were two different nations, but they were 'equal'. This was a strange concept of equality. He feared that in an undivided India Hindus would rule forever. He wanted a Muslim majority Pakistan if the British were to leave India.

The long and short of it was that Jinnah was an indirect beneficiary of the Quit India movement.

An illustration of the Law of the unintended Consequences!

To what extent was the Quit India movement effective in achieving its goal?

Did it force the British to leave India? There was a five-year gap between the launching of the agitation and the British quitting India.

It would appear that the British were not fully or effectively discouraged from retaining India as a colony.

To a certain extent it might have emboldened the common man to actively agitate against the British.

It wasn't as if the Quit India movement did not achieve anything: It made thw average Indian fearless of the British.

Thereafter, most Indians started looking upon Independence as an achievable goal and the British knew that they would have to often employ force, progressively more and more, just to govern.

So, what happened between December 1942, and August 1947 that persuaded the British to leave? There are a number of reasons:

The formation of the Indian National Army shook the British. They knew they could no longer rely on Indian soldiers. The uprising of the Royal Indian Navy in 1946 made things worse from the British point of view.

They concluded that it was time to quit. They had not forgotten 1857, and knew the consequences of ignoring the disenchanted armed forces.

Field Marshal Wavell, the then viceroy, was a shrewd man. He knew the British were not welcome in India any longer, and could only stay on by using greater and greater force which was no longer accessible to the British.

So, it was best to 'split and quit'. And that is exactly what they did.

Lieutenant General Ashok Joshi (retd) served in the Indian Army for three decades. He was the Chhatrapati Shivaji Fellow at Pune University and author of Restructuring National Security published by Manas Publications in 2000.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com