| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Aruna Shanbaug's death has again opened up the euthanasia conversation in the public domain. For a health care discourse often dominated by inane news, this is not such a bad thing,' says Dr Sanjay Nagral.

'Aruna Shanbaug's death has again opened up the euthanasia conversation in the public domain. For a health care discourse often dominated by inane news, this is not such a bad thing,' says Dr Sanjay Nagral.

Six months back I had to perform emergency surgery on a businessman for intestinal gangrene. He was 75, had diabetes and had previously suffered from two heart attacks.

Over the last few years his activity was severely restricted and was largely bed ridden. During the surgery I had to remove around 75 per cent of his intestine as it had turned black due to lack of blood flow.

Post-operatively he was put on a ventilator as is often the case in such situations and had severe infection resulting in poor functioning of his heart and kidneys.

He was being treated by a team of five doctors in the intensive care unit of a large private hospital. A week from surgery he was still hooked onto a ventilator and was being dialysed for kidney failure.

I had been talking to his family about the grave nature of the illness and the fact that even if he recovered, his life would be severely compromised.

The loss of a large part of the intestine would make it impossible for him to eat normally.

"Please try everything doctor, we want you to save him at all costs" was their initial response.

Five days later he was being pumped with five antibiotics, infused nutrition through his veins, the pumping of his heart supported by drugs. All this while he was sedated as he was unable to be taken off the ventilator.

I was growing increasingly uncomfortable with what we were doing and expressed this to my colleagues. I suggested to the family that things were not looking good and that what we were doing was probably futile.

I was trying to build a case for a slow withdrawal of care. My colleagues warned me saying 'This is against the law.' The family though confused was gradually beginning to come to terms with the situation. By this time the hospital bill had crossed 20 lakh rupees.

In the third week of the illness with no sign of improvement, the patient's grandson came down from the USA. After hearing me out he said, "I agree with you we shouldn't drag this on for long, I will convince my family members to consent to pull out."

The next day they conveyed their decision to me that they wanted us to stop treatment. I replied that although it is difficult to disconnect the ventilator we could stop other supports, an act vaguely termed 'passive euthanasia' in India.

I put this down on the case sheets and requested my colleagues for their concurrence. Most of them refused to commit anything on paper again warning me that this was 'not allowed.'

I then suggested to the family that they approach the hospital management with a written request. Upon doing so they were told a firm no. It is against hospital protocols and the law came the stock answer.

When they persisted they were told that the only way out was to take the patient out of the hospital by resorting to a strange practice of Indian health care called 'Discharge against medical advice.'

"Where do we take him? Why not let him go?" The family pleaded. The bill was also mounting by the hour.

Finally we worked out a plan. They would request discharge and take him home. Who will give the death certificate was the next question. Fortunately, I spoke to their family doctor who understood the scenario and agreed to sign a death certificate.

Two days later after much bitterness, stress and paying of the bill which was by now around 30 lakhs, they put him in an ambulance with a portable ventilator. They called me later to say that his life ended on the way in the ambulance on Mumbai's Bandra Worli Sealink.

Aruna Shanbaug's death in Mumbai's KEM Hospital has again opened up the euthanasia conversation in the public domain. For a health care discourse often dominated by inane and superfluous news, this is not such a bad thing.

For those on the frontiers of health care delivery, it throws up many dilemmas and contradictions. For example, there are many Arunas in persistent vegetative state who die much earlier as they don't get the care she got as a special case.

As a young doctor at KEM Hospital, I was witness to the amazing care she got from the nurses of Ward no 4. Aruna's death would have gone unnoticed had it not been for the doughty Pinkie Virani. Her book and her court case.

My patient's death though not a textbook case from the euthanasia discourse is a much more common scenario in the increasingly privatised Indian healthcare. There are also many patients with terminal cancers who undergo questionable and futile treatment without being offered humane palliative care.

What would be the scientifically valid, error free and yet humane framework for the implementation of the passive euthanasia judgment that Pinkie Virani has managed to get from the Supreme Court?

The Indian healthcare scenario has an extraordinarily complicated but distressing dichotomy which also comes up in the context of euthanasia. Thousands of rich patients are offered futile care in private hospital settings as the system reaps profits from prolonging treatment.

On the other hand, lakhs of the poor are subject to an involuntary and systemic form of passive euthanasia for diseases that can be treated because they cannot afford the cost of care.

So whilst as a society, we slowly attempt to move towards crystalising our ideas on complex issues like euthanasia, it would be worthwhile addressing the biggest confounder peculiar to India.

This is the lack of a publicly funded universal health care system which is free from the influence of the market and hence takes most decisions in the patients' interests.

This is not utopia but an option implemented by many countries. When healthcare stops treating disease as a commodity and a business opportunity, it will also stop treating the end of life in the same framework.

An ethical, humane as well as culturally sensitive framework on euthanasia is then likely to emerge.

Sanjay Nagral is a practising surgeon in Mumbai.

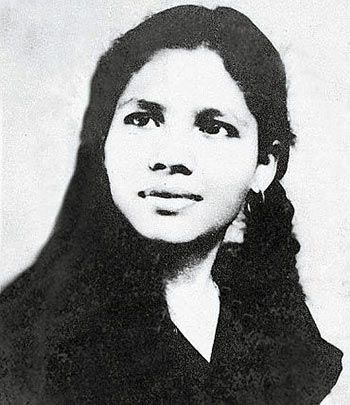

Image: Aruna Shanbaug who passed away after being in coma for 42 years.

ALSO READ: