| « Back to article | Print this article |

Their lives, spent in a state of chronic hunger and deprivation, are a telling indictment of India's porous social security net, says Geetanjali Krishna.

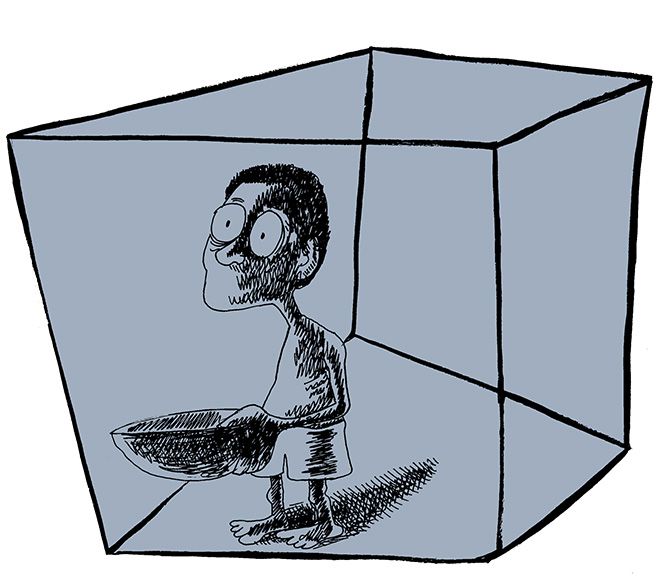

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

On July 24, 2018, when three siblings, Mansi (8), Shikha (4) and Parul (2) died in a tenement in East Delhi, their autopsies revealed that they had neither food nor water in their bodies.

Four days after their death, I accompanied the folks from the Delhi Right to Food Campaign and Center for Equity Studies on a fact-finding mission to Mandawali where the children lived and died.

The experience left me feeling confused and convinced at the same time.

Here's what we found:

When they died, the girls had been living in a room inside a two-storey building with 28 such rooms and a common toilet in Pandit Chowk, Mandawali.

The neighbours reported that the family had arrived there three days before the children died. They'd had no contact with them, for apparently, all three had been sick since they moved in.

Their father Mangal had left after spending one night in the room with them, and hadn't been seen since. The prevalent notion was that the mother seemed very weak as well, and somehow mentally challenged.

When I asked why they thought so, one of them said it was because she had short cropped hair. There was an anganwadi barely 50 steps away, but since the children had arrived three days ago, sick and on the weekend, they weren't enrolled.

Our next stop was the garage from where Mangal used to rent rickshaws at Rs 50 a day. Several rickshaw pullers here had known Mangal and his family well.

Till four years ago, Mangal had a small dhaba. His fortunes turned, and he was forced to become a rickshaw puller. Bad luck dogged his footsteps, and he took to alcohol.

His rickshaws were stolen twice and the second time forced him to leave the room he had rented in Gali number two, Saket Block, Mandawali, to the room of a friend in Pandit Chowk where his children eventually died.

Everyone knew the family in their old neighbourhood in Saket Block, and that they were having trouble making ends meet.

The eldest daughter Mansi was enrolled in school and received a midday meal but she had been irregular since the school reopened after the summer break (during which time no midday meals were given anyway).

There wasn't a functioning anganwadi nearby, in the old neighbourhood, which the younger two children might have accessed. And the family, like many others we met that day, did not possess a ration card.

The picture that emerged wasn't just of three children with a largely absent, alcoholic father and a physically weak, possibly mentally ill mother. It was of a family belonging to India's vast unorganised sector that faced a series of economic shocks with no systemic support.

They weren't the only ones. Most of the neighbours and Mangal's fellow rickshaw pullers we met, displayed the same vulnerabilities.

With no fixed income, ration card or access to anganwadis, they too were teetering on the brink of the abyss Mangal's family had just fallen in.

As Harsh Mander of CES pointed out, the need of the hour was a detailed 'social' autopsy, not another one of the poor girl's bodies for further signs of starvation.

For their lives, spent in a state of chronic hunger and deprivation, are a more telling indictment of India's porous social security net than their deaths actually are.