Home > News > Interview

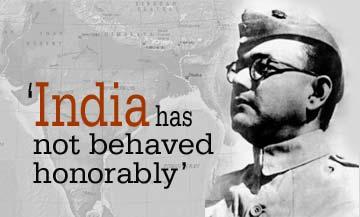

The Rediff Interview/Anita Bose Pfaff

May 11, 2005

The first part of the exclusive interview with Anita Bose Pfaff, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose's only child:

The Introduction

How old were you when your father saw you last?

I was only four weeks old when he saw me last. I was born in 1942 and he left Germany [Images] by submarine for Southeast Asia in early 1943. So he saw me when I was very little. When he most likely died in an air-crash in what is now Taiwan -- in August 1945 -- I was about two and three quarters (years old].

How did your parents meet?

It was in 1934 when my father was in Vienna to seek medical treatment (he had been in jail in Mandalay, Burma, because of his struggle for India's independence). He was sick and getting quite weak and was released on condition that he would leave the country to get medical treatment.

Vienna at that time was quite a famous centre for medicine. So he came there during the period when he had his treatment. At the same time he was working on a book. He looked for a secretary to type his manuscripts and approached an Indian student to ask if he knew a lady who might do this for him.

The student was running a discussion course in which my mother was a member. So he recommended her and this is how they met.

After that, was your father in and out of Europe between 1934 and 1943?

You could extend that period that far; in and out during the 1930s. Then he had more extensive stays in India. First of all, he was Congress (party) president in 1938 and got re-elected in 1939 against the wishes of Mahatma Gandhi [Images] who had set up another candidate. After that, the Second World War started in Europe and during that period there was not that much traveling back and forth.

In 1941 my father returned to Germany by an adventurous route. He had been interned at home in Kolkata (by the British) but made an escape from there, traveling in disguise as a Pathan from northern India to the North West Frontier Province (now in Pakistan), and up to Kabul. There he had the support of the German and Italian embassies to give him an Italian passport. Accompanied by a German diplomat he traveled across the Soviet Union, which had not entered the war and allowed him to pass through to Berlin.

What do you know of your father's role in forming the Indian National Army that fought the British?

Actually, the INA had existed before his reaching Southeast Asia, but it had not picked up so well. One of the persons actively involved in it -- Ras Behari Bose -- wanted my father to take over. Ras Behari had lived in the region for some time and was married to a Japanese lady.

The INA wasn't just made up of former prisoners of war released by the Japanese. There were also many Indian plantation workers in Malaya who joined up; some of the recruits were prisoners of war and the Japanese handed them over to the INA. Quite a few joined up because they wanted to do something for their country.

What was unusual for those days was that the INA had a women's corps. My father was quite modern in his views and he had always felt that India had under-utilised resources. One was women and the other was the downtrodden, the workers, who were not recognised as a human resource.

So the INA had a women's corps of 1,000 women; its commander was Dr (later Colonel) Lakshmi Sehgal. At that time she was Dr Swaminathan from south India who had gone to Southeast Asia. She is still alive. In fact, she was one of the contenders for the Presidency of India (Colonel Sehgal was the Communist parties' candidate for President against A P J Abdul Kalam in July 2002. She lost the election).

The INA then saw action on the Burma Front.

The INA reached Indian soil in what is now called the Northeast provinces. There was a battle of Kohima and Imphal where they were defeated (by the British) and had to retreat. Quite a few died. Politically they were more successful as subsequently released documents have shown.

In post-Independent India the INA's role was played down. The official evaluation was that its activities had little effect. Militarily speaking that was true because the army was not that well equipped, but the British made a great political mistake by putting three INA officers on trial at the Red Fort [Images] (in Delhi), expecting that people would look down on them as traitors. The opposite happened and the trial publicized the efforts of the INA, which had previously been censored.

Until the trial little had been known of the INA or the Government of India in exile in 1943 when they tried to send food to Bengal during the Great Famine. All of a sudden this trial made everything known and it revived the struggle for independence in India, which had been lagging because the leadership of the Congress party and other groups mostly had been imprisoned. Their efforts like the Quit India movement had not been successful and so this gave a new dawn to the movement.

As a consequence of the INA's efforts, large numbers within the British Indian Army -- which was not just British but for the most part Indian -- became unreliable. There was a mutiny in Bombay (by the Royal Indian Navy), which showed the armed forces could not be depended on. The administrative system was what had controlled India and with the army unreliable the British realised India could not be held as a colony any more. This led to the transfer of power. It was meant to have taken place a few months later, but it was brought forward to August 1947.

You could therefore say the INA had this effect of destabilising the British hold on the Indian army and reviving the independence movement within India.

The INA certainly has its place in Indian history.

When the first few INA soldiers returned to India they were treated as heroes, but I must say in the later stages India has not treated them very well. The INA veterans were not recognised as army veterans and for a very long time they were not even recognised as freedom fighters, which meant that certain benefits such as a pension and free rail travel were denied to them. Many members of the INA were reduced to poverty and some of them died in hunger. These were simple people and could not find their way that easily in the country to which they returned.

India has not behaved towards this group in an honorable or fair way.

Part II: 'Gandhi was no saint'

Image: Uday Kuckian