Home > News > Interview

The Rediff Interview/M J Akbar

July 05, 2004

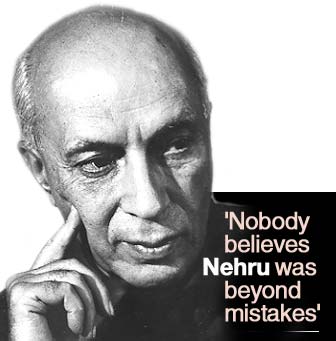

Forty years ago, India's first prime minister passed into the ages. On his death anniversary, May 27, rediff.com commenced a series to evaluate Jawaharlal Nehru's legacy. M J Akbar, editor-in-chief of The Asian Age and author of Nehru: The Making of India, believes it was Nehru's vision that shaped modern India. In an exclusive interview with Senior Editor Ramananda Sengupta, Akbar recounts anecdotes that reveal the personal bravery as well as the foibles of India's first prime minister, and rebuts the charge that it was Nehru's Socialism that kept India backward for so long. What would you consider Nehru's single most important contribution to India? His most important contribution in a life full of contributions was a clear establishment of a vision in which to lift India from the 18th century towards the 21st. One of the things that we underestimate in governance or public life is the commitment to the future. Governance very often becomes a matter of tackling day-to-day management, particularly in a complex country like ours. Why do you say 18th century? There is a very interesting statistic in Paul Kennedy's book, Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. It says that in 1790, almost a hundred years since the death of Aurangzeb, India had 23 percent of the world's manufacturing output. And Britain had 1.8. In 1947, Britain had 23 percent of the world's manufacturing output and India had 1.8 percent. That was the kind of impoverishment inflicted on India by British imperialists. Food shortages were always a part of India's chronic problems. But famine on the scale that India witnessed under the British was unprecedented. And quite a few of these famines were man-made. The Indian national movement, just before the British left -- and this fact doesn't seem to register on anyone because we haven't found enough historians to actually highlight them -- three million people died of famine in Bengal. It's an extraordinary figure. So the people who inherited this nation had very very serious problems on how to tackle this sort of thing. So how did they tackle it? In 1948, there was again a food shortage in the country. Jawaharlal was making his first trip to America. And one of the things that was suggested in the Cabinet was that he should ask America for food. He refused. 'I am not making my first trip to America with a begging bowl. We have to sort this problem out ourselves,' he said. To carry both the level of self-confidence, not vanity but pride in one's nation, to look at the future, to try and develop the dynamic infrastructure required for that future, to stay in a country steeped in religion and, having watched religious emotions play havoc with the unity of the country and the people, to stand up and take positions against what might be called fundamentalism, to seek to define a new language by saying that the steel mills and the dams were the temples of modern India, this required conviction, courage and the confidence that the people would actually believe in good government, a commitment to economic principles, and the conviction that swaying them with religion was not just wrong but injurious... these were remarkable convictions that shaped India. Jawaharlal's best years were from 1947 to maybe 1958-1960. He also had sheer physical courage. There's the story of how during the 1947 riots, he was travelling in his Ambassador car as prime minister and he suddenly saw a Muslim tailor being attacked in Chandni Chowk. And he stopped the car and just charged in. In those days they didn't have the SPG [Special Protection Group, elite commandos who guard the prime minister today] and they didn't have helicopters saving prime ministers. He just charged in using his baton or whatever he used to carry. I'll tell you another story. And this again requires courage. The IB [Intelligence Bureau] asked him to remove Muslim cooks from his kitchen, because of the angers of Partition and so on and so forth, and I suppose the IB was right in doing what it sought to do. Jawaharlal completely refused, saying there's no question of it. In this respect, his daughter Indira Gandhi did the same. She refused to suspect all Sikhs after Operation Bluestar. One of the charges often levelled against Nehru relates to his economics. It is said that India remained backward for so long because of his Socialist system... I think that's very very unfair. Every 'ism' is basically a reflection of the moment. There's no permanent ism. The only permanent ism can be faith -- like Hinduism or Islamism. An economy theory or philosophy is not Moses' Ten Commandments. In the 1950s, the country needed the investment in infrastructure, in steel, etc which the private sector never had. So where was the private sector going to deliver on these? There was just one Tata. But where there was private sector in existence, he didn't go around nationalizing it. He didn't nationalize Ambassador cars. He just produced state investment in those areas... what did he expect, that the private sector would produce dams? The reason why he believed in Socialism was social justice. It was not Communism. He was not bringing Stalinism into the country. I believe that if Jawaharlal Nehru had lived into the 1970s, he himself would have changed with the times. Much of the Socialism that we attribute to him actually came during Indira Gandhi's time, when under the advice of certain people whose names are best forgotten, she went to the point of once even proposing that the wheat trade in the country should be taken over by the government. This is all post '69-70, when politics took over economics. The other charge against him is that he internationalized the Kashmir issue by taking it to the UN. That was a Cabinet decision, and in that Cabinet, Sardar Patel was there. There is a viewpoint and a Cabinet decision. The Kashmir issue is not a simple matter. To begin with, if it was going to be sorted out, it was never really tackled by the home ministry before Partition. When all the other princely states were being integrated, Kashmir was left as a problem to be sorted out later. Deliberately, consciously. In fact, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote a very perceptive letter to Sardar Patel – when the prime minister writes to the home minister, he is doing it very consciously – and Jawaharlal wrote to Sardar Patel urging that Sheikh Abdullah, who was still in jail, be released, since otherwise Pakistan was being 'tempted' to take a very adventurist course. This was before Pakistan's attack on Kashmir. Lord Mountbatten was still an executive authority in India at that time. It was not a completely Indian government. Generals in the Indian Army and the commander-in-chief were still Englishmen, both in India and Pakistan. It was a twilight time, a time of change. It was Lord Mountbatten's intervention that not only enabled us to send the army to turn back the raiders, but it was also the quiet British intervention that prevented the Pakistan Army from obeying Jinnah in 1947 and rushing to Kashmir, giving us a very critical time frame. But as politics, Kashmir really began to be lost in the sense when Mountbatten persuaded the Cabinet that the only way out of war – war was not something that anybody wanted, they had just recovered from the Second World War – was to take it to an international dispensation. In that too there was a complication, there were many views on the subject. There was still faith in the UN, and Partition itself was an international problem. I believe, of course, that at that time there would have been tripartite talks between India, Pakistan and Britain if Pakistan had not sent raiders. So Pakistan actually lost by sending raiders. There is no human being who is perfect. There is nobody who admires Jawaharlal Nehru, something I do deeply, who believes that Nehru is beyond mistakes. What about the war with China? I think generally that is where his leadership weakened, wobbled, and finally collapsed. He had very little sense of the general state of our defence, and here he became a victim of his blind faith in Krishna Menon. Menon was a great man, no doubt about that. But he was not just glorious, he was also vainglorious. And [because of] their long association before, in the freedom movement and government and so on, Jawaharlal thought all the time that any criticism of Krishna Menon was criticism of Nehru himself, and so Menon was always being set up. He really did not have any understanding of India's strength and when Chou En-lai came for the talks, which failed... incidentally, the man who took the hardest line on China was Morarji Desai – in the event it was Morarji who took a stand and broke off the China talks... So did the war with China actually break Nehru as a person and lead to his early demise? Yes, I think that is true. He never really recovered from that defeat, although like Nasser after '57, the Egyptians rallied to Nasser, similarly Indians rallied to Jawaharlal, but he was never himself after that. Would Nehru be able to recognise the Congress party as it is now? No. Image: Uttam Ghosh Nehru, 40 Years On

|