| « Back to article | Print this article |

'That only a certain Mumbai story -- look at Salaam Bombay and Slumdog Millionaire for other examples -- gets made when an international audience is as much a target as the desi viewer, should invoke questions of representation,' notes Vikram Johri.

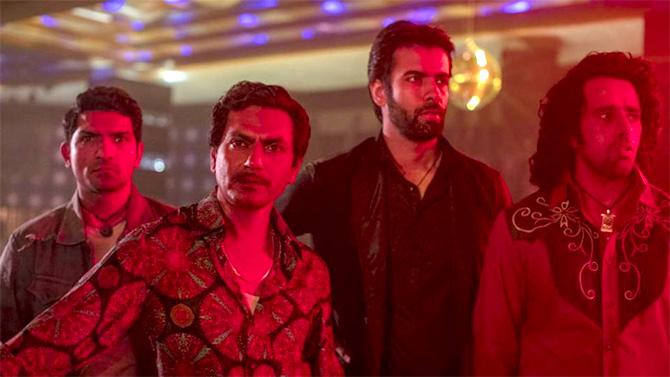

In the first scene of the newly released Netflix adaptation of Vikram Chandra's novel, Sacred Games, Jojo Mascarenhas' (played by Surveen Chawla) Pomeranian is thrown outside an apartment building by her consort Ganesh Gaitonde (played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui).

In the original novel, the poor creature is thrown out of a moving car, which does not make it less painful, but at least on the page, one is spared the harrowing cries of the dying animal.

That first scene encapsulates this Phantom Pictures' adaptation.

Take what you need from the original, pack it with darkness to give it the aura of respectability, mute the colours to make it eye-catchingly dreary and purportedly seductive, and you have the test case for Netflix's foray into original programming from India.

The story is fairly straightforward.

Inspector Sartaj Singh (played by Saif Ali Khan), a police officer down on his luck, receives a call from dreaded gangster Gaitonde moments before the latter's death.

The message, about a possible attack on Mumbai, is cryptic, as is Gaitonde's reason for seeking out Singh.

Over the course of the novel -- and this eight-episode series -- the nature of the threat and the origin of Gaitonde's backstory are discussed.

Also present is R&AW (Research and Analysis Wing) agent Anjali Mathur (played by Radhika Apte), certain that Gaitonde's death is not, as is believed by some in her agency, the outcome of a gang war. She is proved right ultimately, but the denouement is never the most interesting sequence in an Anurag Kashyap production.

Here, too, we are expected to sit back and soak in the abuse-laden authenticity.

The show is certainly stylish.

Set in Mumbai, it uses the city's easy accommodation of dual opposites -- rich and poor, moral and amoral, power-hungry and already powerful -- to considerable effect, fashioning a tale in which the highest rungs of society are shaped by, and stay beholden to, the griminess of the street.

Gaitonde builds his first fortune by laying claim to a garbage dump in what is a too-apt metaphor for both the plight and promise of this megapolis.

In its treatment, Sacred Games diverges significantly from the book that inspired it, in that it isn't strictly about the men who occupied the book's centre stage.

Siddiqui’s Gaitonde has the cavalier cool of that other, classic don he played, Faizal from Gangs of Wasseypur as opposed to the Gaitonde of the book, a mousy interloper who comes to rule Mumbai through sheer cunning.

Similarly, Khan's Singh is the upright centre of a world gone to moral waste.

In an early scene, he is beaten by a fellow cop for his refusal to go along with the police department's version of a fake encounter.

We root for him for this reason, for shining a dim light into the pervasive darkness. The book's Sartaj is a greyer character, willing to do right but not so certain of his motives.

The series runs a countdown on the screen, as the characters and the viewer mark the days before Gaitonde's enigmatic warning comes to pass.

This gives the show the look and feel of a thriller, something I am not sure Chandra had in mind when he imagined his novel.

While you keep your eyes peeled for the next surprise discovery, you do not necessarily learn as much about the deep, provocative world Chandra wrought in his doorstopper.

Even so, what cannot be escaped is the political nature of the work.

The unkind references to Rajiv Gandhi have already hit the headlines, which is a surprise because most of it is altogether mild compared to, say, the criticism directed at Indira Gandhi by Rohinton Mistry in A Fine Balance. Heaven forfend if that book were ever made into a television show.

But I use 'political' in a different sense.

Sacred Games is a novel of the 20th century, of an India where Mumbai, then Bombay, offered the prospect of escape from grinding poverty only if one were willing to strike a bargain with the devil.

From the rebellion of his childhood to his domination of the Mumbai underworld, little of satanic import is left out of Gaitonde's story.

In a casting choice dripping in symbolism, Sunny Pawar, the young boy from transnational adoption drama, Lion, portrays Gaitonde's childhood.

That only a certain Mumbai story -- look at Salaam Bombay and Slumdog Millionaire for other examples -- gets made when an international audience is as much a target as the desi viewer, should invoke questions of representation.

It can be argued that each of these products showcases an India, and certainly a Mumbai, that was -- and perhaps remains -- a historical reality for vast swathes of our population.

Indeed, the famed 'triumph of the spirit' narrative that is so often bandied about for Mumbai, and not just on reel, emerges from the real, material problems that continue to plague this country.

Yet, one would like to believe that India has also sufficiently changed over recent decades to offer less grim, less crime-infested narratives about climbing the social ladder.

I imagine an international viewer appreciating Kashyap's visual style, the tightness of the action or the befitting background score.

I wonder, though, if the all-powerful Netflix would give this viewer other stories before he makes, and hardens, his impression of India.