| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Every time I watch Sholay telling myself that it is nothing more than a 'brazen potboiler,' the movie works. However, each time I take it for this iconic masterpiece, Sholay falls short; terribly short,' says Sreehari Nair.

The most interesting aspect of Shekhar Kapur's Sholay-specific quote ('Indian film history can be divided into Sholay BC and Sholay AD') is that it seems more like one of those IMDB Fanboy quips, than something that Kapur at his analytical best would say.

The most interesting aspect of Shekhar Kapur's Sholay-specific quote ('Indian film history can be divided into Sholay BC and Sholay AD') is that it seems more like one of those IMDB Fanboy quips, than something that Kapur at his analytical best would say.

In pure marketing terms, the quote has a nice ring to it (My guess is, it would blare out of a re-release poster of the movie. I also won't be surprised if Wikipedia already has it mentioned on its Sholay page).

But try checking the veracity of what those words hint at.

To me, the argument presents Sholay as this big Game-Changer; our very own Citizen Kane if you may agree. The fact however -- in contrast to what the party line would like you to believe -- is that Sholay didn't really transform the landscape of movie-making in India. It may have altered our movie-watching consciousness. But even most of those alterations, mind you, haven't particularly done our sensibility any good.

Yes, it gave us a villain whose tics we continue to love. Yes it gave us one amazingly shot-and-assembled train-fight sequence. Yes, it -- although in a very obvious sort of way -- gave us some tender moments between Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan (the lantern-dimming scene, despite its eagerness to wow us, does have a postcard-like quality about it).

However, even as it got all of the above things right, the aching truth is that the poetry of Sholay -- like that 'pop-psychology pool' we all swim in together -- hits us more as 'self-serving.' In short, Sholay's poetry has never really spawned other good poetries.

As I see it, Shekhar Kapur's own Bandit Queen has had a 'more decisive and positive impact' on the climate of movie-making in India. Movies like Satya -- in its portrayal of tranquility being suddenly disrupted by a set of invisible gunmen; in the way it shows the co-existence of 'domestic intimacy' and the 'madness on the streets' in its illustration of how 'modern warfare' can suddenly turn into 'tribal warfare- -- owe silent but sure debts to Bandit Queen.

And Satya itself became the prototype for some of our best post-millennium works such as Maqbool and Ab Tak Chappan.

If there's anything such as a case that can be made for such truly great movies, it is that they expand in your head, slowly. These movies let you draw your own sub-textual analyses. Beyond just quoting their lines, their relevance shows up in your own life (this is as true of 'trashy movies, done right' as of 'bonafide masterpieces'). Even your misreading of them, offshoots something new, something vital.

Sholay, however, doesn't offer you any of the above pleasures.

To the movie's credit, I don't think it intended to. For every time I watch Sholay telling myself that it is nothing more than a 'brazen potboiler,' the movie works. However, each time I take it for this iconic masterpiece, Sholay falls short; terribly short. Meaning, a movie with a stature built on the entire premise that it was a gigantic money-spinner in its time. 'We saw it playing in a theatre for 5 years. Who are you to disown it over one viewing?' aficionados seem to ask me.

Etiologically speaking, Ramesh Sippy's blockbuster was essentially Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai made more digestible and churned up. The approach was roughly like Sergio Leone's approach to Kurosawa's Yojimbo (remade as A Fistful of Dollars): Take a story with mythical undercurrents and present it as a case-study for machismo.

What got lost in those two instances of homogenisation is the social angle that set the base for the machismo to play out.

In both Kurosawa's Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, there are two kinds of conflicts. The central conflict is, of course, one that arises out of the 'Good Guys' standing up to the 'Bad Guys.' But a less obvious conflict is the simmering distrust that the villagers have for their supposed saviours. It's the second kind of conflict that builds interior tension, helps Kurosawa's narratives discover melancholy even in their exaltations and finally makes those movies transcend their genres.

However, because it undercuts the internal conflict, Sholay, like Leone's version of Yojimbo, has to get to its viewers by relying mainly on the 'Giant Sweep' that characterises most modern-day Westerns.

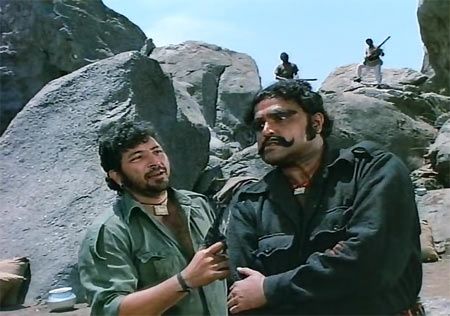

Now, on the topic of Sholay's most famous iconography. I call Gabbar Singh an iconography, and not a character, because everything he does in the movie is essentially a piece of theatre. What makes his theatre interesting is that while everyone else in Sholay (from Thakur to Basanti's steed) is caught up in the self-seriousness of their pursuit, all Gabbar is solely interested in, is playing the part he has designed for himself.

For a country that was still not out of the War of 1971 and slowly getting entangled in the Emergency of 1975, Gabbar represented a hip version of the country's disillusionment with idealism. He was a both a 'product of' and a 'misfit in' the very society that created him. He is both, Sholay's charm and its curse -- the one factor that keeps most discussions about the movie alive, to date.

When I was growing up, 'Sholay' was the standard answer that most people had to the question: What is your favourite movie? Today, most of these very people cite the movie as 'one of their favourites. The attachment for the movie that was once considered 'venerable' is today 'verily sentimental.'

Quite often, interviewers stare blankly at celebrities when they make a list of their favourite movies and exclude Sholay. Some celebrities don't get the blank expression and wait for the next question. Others are more kinesthetically gifted, and they are quick to add, 'And, of course, Sholay.' This response makes the interviewer feel like he or she is on familiar turf once again, and the interview itself starts to assume a more benign tone.

Sholay's popularity is undeniable. However its timeless appeal is largely mythologised. It's when we start ascribing greatness to the movie that the entire discourse becomes forced. You feel like you've outgrown the movie -- a feeling that you can't entirely blame the movie, for propagating.

Yes, Shekhar Kapur's cutesy 'BC and AD' quote when approached obliquely does make sense. For Sholay isn't exactly caught in a time-warp. But our fascination for it definitely is.

OUR SHOLAY SERIES