| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Kaala's sin is not that it is presented as a mouthpiece for its director Pa Ranjith's political viewpoints, but that it makes a travesty of them.'

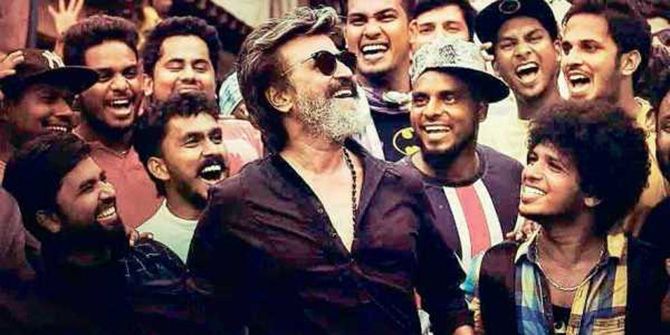

'Ranjith turns Marx into merchandise, all the while functioning as a hired hand for Brand Rajinikanth,' argues Sreehari Nair.

In Pa Ranjith's Kaala, Bihar-born Pankaj Tripathi plays Patil, a police officer who hectors civilians in Tamil. Ah, the number of flaming hoops of falsification he has to leap through: Even for a great actor like Tripathi, it could not have been easy.

The falseness in Tripathi's character, in a way, is the preamble to Kaala's dishonesty. For this is a movie whose artistic compromises exist to bend its righteous spine.

Even the negative reviews seem to have got it wrong.

Kaala's sin is not that it is presented as a mouthpiece for its director's political viewpoints, but that it makes a travesty of them.

Ranjith turns Marx into merchandise; showboating his Leftist readings, all the while functioning as a hired hand for Brand Rajinikanth.

Look, there's Ranjith pushing us beyond the Puritanism of our textbooks.

And where does he lead us to? -- A Puritanism of the Revisionist kind.

There he is, pulling down the pillars of a self-serving temple. And how does he celebrate the conquest? -- By replacing one deity with another.

The essence of totalitarianism -- when you get down to it -- is one person telling everyone else what to think and how. And in Rajinikanth's all-knowing, all-powerful, all-seeing Karikaalan, we don't get an antidote for totalitarianism as much as a new ambassador for it.

Ranjith appears to be stacking the deck to show us an entire world of oppression, but because his 'oppressed' are without any sustained shading whatsoever, there's no way for us into the politics of the movie.

In Rajeev Ravi's flawed but wonderfully illuminating Kammatipaadam (another movie that took on the subject of land mafia), Ravi was very careful that his 'oppressed' weren't made mousy. We weren't spared the foibles of the oppressed that made possible their exploitation.

In one of Kammatipaadam's key sequences -- one that tells you about the depth and humanity of Rajeev Ravi -- the lead character, Krishnan (Dulquer), visits a low-caste friend upon learning the death of his grandfather, and the slightly mourning friend offers Krishnan some arrack to drink.

The difference between Pa Ranjith and Rajeev Ravi, I guess, is the precise difference between someone who transposes Das Kapital onto sensational newspaper stories AND someone who uses the text to look into himself and the world.

To these reservations, arise the natural quibble, 'But Kaala's just a massy, masala movie, macha.'

No macha, it isn't -- and it cannot be enjoyed as one either; because Pa Ranjith's 'supposed' political views constantly undercut the pleasures of the film and his two dharmas cancel each other out.

And here's the irony.

Despite all that charade of 'social conscience,' if there's any subtext to be unearthed in the movie, you'll find them in the masala bits.

In what I thought was Kaala's best scene, Karikaalan, in a drunken stupor, taunts Sayaji Shinde's 'minister character,' by repeatedly pointing his finger at Shinde, and asking those around him, 'Who is this guy?'

Shinde's the stiff trying to get Karikaalan to behave (inside a police station, no less) and every time he (Shinde) finishes his 'Head Boy's Speech,' the class rogue Karikaalan takes the wind out of the snoot's sails.

'Who is this guy?'

Each time that line is uttered, its comic pitch gets amplified, and it slowly becomes a statement of grand heroism.

'Who is this guy?' is the 'Who are you?' of times yonder (said, here, not with a growl but with a catnip smile) and it brings flooding back, all our hoarded memories of masala one-upmanship!

The punch-line also reveals what this movie, as every Rajinikanth movie unfailingly, expects from Rajinikanth: to get star-struck on himself.

The shared sentiment in the breast of the every Rajini fan seems to be, 'How could we love this man if he didn't love himself enough?'

And yet, watching Kaala, I could not help but feel that Rajini was perhaps growing tired of nurturing this self-love; that the final straw of narcissism was upon us.

When he is the focus of a frame, there is a sense of tiredness that now comes screaming out.

And yet, look at how he 'behaves' when he's just one among a crowd: when others argue in the foreground and he just sits there bored by their ranting or smacking playfully the backsides of Kutty Rajinis.

Is he finally begging us to leave him alone?

Should we free him up and use him smartly to also tell the stories of those around him?

It is in viewing scenes dictated not by Rajini's domination, but by his behaviour that a painful hunch hit this critic: Are we looking at a truly great actor who has, for years now, been held hostage by the movie camera?

Correspondingly, is the landscape of 'Realistic Tamil Cinema,' that took shape in the last decade or so, yet to break free of the histrionics of old-school Tamil cinema? (Is this why the 'cool killings' in some of these movies often get mistaken as a representation of 'reality'?)

In Kaala, these contrasting, half-formed sensibilities don't find a new expression; instead, they make the movie an experience you can neither consume as a serious work with something original to say nor spit out as a piece of bubblegum, now rendered juiceless.

Ideas and styles are developed but not followed through.

The fight for Dharavi is introduced as a three-way fight (Fought between builders and politicians working in collusion; easy idealists; and the worldly-wise typified by Rajini and gang).

However, it gradually de-evolves into a two-way fight, but without any clear illustration of the changing tensions in the internal power structures.

Who needs interiority when you have a hero who sashays through the rain wielding his Japanese umbrella like a Ninjatō?

What is the relationship that Karikaalan shares with his children?

What part of his personality has been passed on to which of his children?

There are no answers (hell, there aren't even questions asked), and so we never really know what it means for the man to lose any of them.

Who needs petty father-son dynamics when the purpose of the patriarch is to spout lines such as: 'Not just my kith and kin; I belong to everyone'?

Pa Ranjith, in one frame, shows off the ultimate gagster touch: A passing shot of Rajini walking through the slums in total darkness, where we barely hear the man's voice (Reads like a small thing, I know; but it takes guts to shoot a Rajinikanth scene without showing Rajinikanth in his full glory).

Ranjith further stages a Ganesha procession sequence with terrific control -- with the nervous camera and the overlapping voices merging in tip-top form.

But, pray, how can someone with such feel for small authenticities then parade a press photographer's rough footage where people are shown to be running in slow motion? I didn't know press photographers edited their sequences as they shot it!

Ranjith begins by capturing naturalistic sounds -- the breeze rippling through leaves; the rain; the kitchen sounds -- but as if convinced that these weren't providing the desired results, he turns his ear in the direction of the ticking clock, the breaking knuckles, and Nana Patekar's chappals that wouldn't leave the carpet without leaving their mark on your external auditory meatus.

The head-tilting, body shaking Rajinikanth comes up against two forces of parodying and they're among the more interesting parts of the movie.

Eswari Rao as the wife, Selvi, is meant to be a stand-in for that section of Rajini fans that loves him, but is also beginning to be cynical of his heroism; the section that treats him both as God and a Shared Joke.

Selvi catches Karikaalan out -- often, on the edge of doing something synthetic; something self-conscious; something naughty.

And there's Nana Patekar's Haridev Abhyankar who responds to Kaala's idealistic musings with a 'Tell me something new.' It's a throwaway line, but has a spirit that the movie should have pursued vigorously. Instead, we watch Patekar slowly, with every passing frame, being turned into a comic-book villianette.

Abhyankar is packaged as a Social Germophobe with power in his eyes and who analyses his election defeat with a quip that runs parallel to his mythology: 'Dirt and filth have defeated me.'

He works effectively as a distant danger, when shot away from us, or when laughing derisively through big hoardings, laughing often at men his goons are in pursuit of.

Yet, as we get up-close, Abhyankar's power and stature seem to diminish, and by the end, Patekar achieves the distinction of overacting through his pauses.

This is a man whose myth catches up with him!

Haridev Abhyankar is the caricature that the Twitter Liberals are holding up as the Right Wing figurehead that Kaala successfully destroys.

What these artless souls don't realise, on a very basic level, is that a Modi or a Trump or an ayatollah is not the cause, but the effect; that they are merely front-men for the divisions that have now become integral elements of the modern world.

What those brilliant Malayalam films of the last three years or a film like Hansal Mehta's Omerta seem to instinctively understand is that only good art -- and not polemics -- has the power to get at the paranoia propagated by the right-wing; and they get at it by portraying these attitudes from inside out.

The time calls for us to not run down the men we hate, but to make our stories about them; and it calls for us to go deeper into ideologies we don't empathise with naturally.

Good art is left-liberal in the true sense of the term; in that, it never aims to make the world a better place: Only less one-dimensional, more profoundly mysterious, and more beautiful in all its numerous contradictions.

And 'massy-yet-messagey' movies like Kaala -- which neither embrace their trashiness wholly nor transcend their numerous tropes -- are a great disservice to both trash and art.

Funnily enough, in trying to make a Rajinikanth film 'for our times,' without a steady accumulation of perspectives or a sense of discovery, what the artist in Ranjith captures is the definitive leftist disillusionment: That which is good for the 'masses' may not always be good for the revolution.