| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Indians are great savers, but they are lousy investors.'

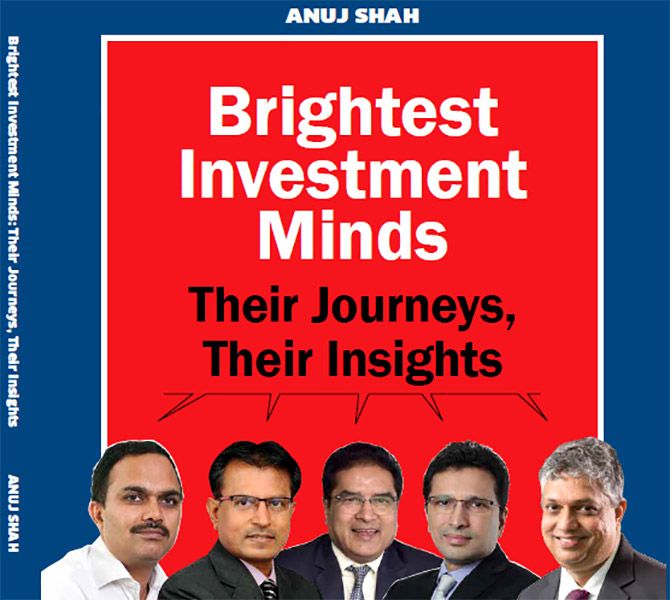

Excerpts from Anuj Shah's Brightest Investment Minds: Their Journeys, Their Insights.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

How many of you, by the time you are 17, get the chance to spend hours together and enlighten yourself with the likes of Raamdeo Agrawal, co-founder, Motilal Oswal Financial Services; Sankaran Naren, ED and CIO, ICICI Prudential Asset Management Company Ltd; Prashant Jain, ED and CIO, HDFC Asset Management Company Ltd, Mahesh Patil, co-CIO, Aditya Birla Sun Life Asset Management Company Ltd; Nilesh Shah, MD and CEO, Kotak Mahindra Asset Management Company Ltd?

How many of you, by the time you are 17, get a chance to work in the slums of India's financial capital and remote Indian villages, with loan disbursement officers of a microfinance lending institute and get exposed to 'real India'?

Anuj Shah, at 17, has been there and done that.

And what has materialised from his interactions with these five wise men is Brightest Investment Minds: Their Journeys, Their Insights, a book that delves on the investment styles, and philosophies of Agrawal, Naren, Jain, Patil and Shah.

'The common thread joining all five of them was their down-to-earth approach towards life and their ability to explain complex theories in extremely simple non-jargoned language,' Anuj writes in the introduction to his book.

Emerging wiser than what he was before meeting these top guns of investing in India, Anuj hopes those whoever reads this book will 'feel the same'.

Investment gyaan from these investment gurus, publishes with the kind permission of Anuj Shah and publisher Dhirendra Kumar of Value Research India Private Ltd.

How to beat a crisis: Raamdeo Agrawal

Raamdeo adopts an extremely practical and rational approach when he sees a crisis. He was caught off guard in the bust, after the early 1990s bull run. But, due to his practical, quality-oriented approach to investing in the stock market, he remained on the profitable side.

For him, and particularly his firm Motilal Oswal, it was the best thing that could happen. The bull-run and the cash it generated helped the firm scale up its business and expand the brokerage business.

The 1992 bull-run was madness because Rs 10 lakh turned into Rs 30 crore.

When the market finally slumped, Raamdeo did suffer eventually, but still ended in the green zone -- green with money.

Although from Rs 30 crore Raamdeo slumped back to Rs 10 crore he had still made a huge net profit across the cycle.

Raamdeo didn't speculate, but remained invested, and that's why the bull run of 1992 saw him ending up still higher.

After reading about cycles, the tech boom and bust was the first time that Raamdeo actually ex-perienced one in real life.

The 2001 bust was also the first time when he felt slightly jittery. After the dotcom era, brokerage businesses were in a slump, and Motilal Oswal experienced its most severe downturn in business, like many other brokerages.

For the first time, the firm faced the issue of cutting staff salaries. However, Raamdeo saw what he had read about in his own surroundings for the first time. Like all markets, there are cycles of excesses.

Benjamin Graham talks about excesses in valuation, markets, and emotions. The experience about excesses comes automatically with time.

In 1992, Raamdeo was caught off guard, but during the dotcom boom of 2000, he often told his US investors that what you are seeing now in 2000, Indian investors experienced in 1992.

"In the stock market you can't create a large fortune in a straight line. Whenever things look too rosy or too easy there is something wrong."

Back in the 2000s, it was difficult to get meetings with foreign investors. For instance, one meeting a day would be quite difficult. But after 2003, things started changing.

In New York, Raamdeo began to have about 8 to 10 meetings daily. Again there was a storm brewing. Suddenly hedge funds started looking at India.

Youngsters started to manage billion dollar funds.

Such was the euphoria that these 'hedge' fund investors would easily give Motilal Oswal Rs 50 million and Rs 100 million dollar trades.

It led the firm to grow 100 times in three years -- from a Rs 10 crore turnover to a Rs 1,000 crore turnover, from a Rs 2 crore profit to about Rs 300 crore currently.

While Raamdeo was hit by the busts, he always ended up on the profitable side in the end by investing in better, sustainable and profitable companies.

***

Dodging the 2008 bullet: Sankaran Naren

Naren dealt with the bust of 2008 much better than the previous one of 1995.

Based on the fact that when he deals with the younger generation they find it difficult to picture how a down cycle will set in after a long prevailing up cycle, Naren notes that until one has seen a bear market one won't be able to imagine how it will come or will find it hard to believe that something like that even exists.

In fact, to Naren it was obvious that the market would fall soon after the 2007 bull run.

In India there are two categories or big companies: Cyclical or brand.

There are no big disruptive Tesla, Google-type companies; there is less of innovation and concept stocks. Therefore, cycles work much easily in this type of environment.

As soon as two parameters, the market cap and the trailing PE ratio, become absurd, the cycle tends to stall, and even turn. This happened in 2008.

However, Naren couldn't communicate this clearly to his colleagues back in those days. He attributes this faulty communication to the lack of clear top-down thinking models.

Naren believes that relative to 1994, he was much more comfortable in 2001 and 2008 because he recognised the concepts of cycles and reversion to the mean.

These concepts formed some of his most important learnings which he drew from the books of investment gurus such as James Montier, Michael Mauboussin and Howard Marks.

Although having a huge cash balance is generally interpreted as either being scared or out of ideas in the investment world, Naren has never refrained from doing so.

In 2010, he had almost 35 per cent of his portfolio as cash when the market PE levels were too high at 23 times for the Sensex, while in December 2011 he had just five to six per cent in cash, when PE levels were steadier at 17 times.

This clearly shows the confidence with which he allocates his assets swiftly.

***

Preventing the 2000 technology bust: Prashant Jain

Prashant is no contrarian, but instead logically looks at prices in relation to future earnings.

"I am not a contrarian; I want to be just a rational investor. From 1995 to 1999, we participated in IT stocks. Everyone made money and even we made money. But when IT became too expensive, we thought that it's enough and we sold. We automatically became contrarian."

Around this time, IT companies were trading at PEs of 200 to 300 times, and began discounting future earnings far into the future.

Infosys was the stock market's darling and was quoting at a PE of over 200. Prashant started to reduce these IT-based stocks from his portfolio.

Those days, a leading analyst wanted Prashant to meet the CFO of a top IT company, who tried to convince him of the big potential of the sector.

After much persuasion, Prashant eventually met the CFO. The analyst hoped that Prashant would once again look at the IT sector favourably. But Prashant stuck to his position, knowing that even while the IT sector as a business had its potential, stock prices were way out of sync with fundamentals.

In those days, Prashant and his colleagues would often look at the valuation ticker and express their doubts about its sustainability. The boys began to doubt the cash-earning models of these businesses.

Rational minds did not see any reason why these companies should be quoting so high.

Prashant and his colleagues even conducted an exercise: Re-pricing IT companies at PE levels of 40 to 50. Even at these, IT companies had to increase their earnings five times to justify their valuations.

As Prashant puts it, "If they had to grow five times, India would have had a large current account surplus. A current-account surplus would mean that the rupee would appreciate, capping the growth potential of IT stocks. Revenues of such companies arose largely from the wage arbitrage prevailing between India and the US. The stocks were, therefore, pricing more growth than what was achievable."

This insight enabled Prashant to minimise the damage in the ensuing IT carnage.

On the contrary, he and his friends delivered stellar returns in their funds: More than 25 percent for five years, till 2003. It was also the year in which Zurich Mutual Fund was acquired by HDFC Mutual Fund, and Prashant was appointed as Head of Equities.

***

The 40-60 balance: Mahesh Patil

Mahesh is known for his bottom-up investing, but later in his investing journey, top-down investing also became an important part of his investing strategy.

Mahesh balances his calls with a blend of both macro outlook and micro-stock selection.

According to Mahesh, if you were to divide his approach statistically, it would be top-down 40 per cent and bottom-up 60 per cent.

When fund managers start managing large sums of money, it's useful to have some macro calls working for you.

"If you have the top-down calls right, you are more likely to get the bottom-up calls right. This particularly is true when there are large sectoral tailwinds which drive stock value."

"Top-down" analysis is now entwined in the investment process for Mahesh's team.

The team routinely meets senior portfolio managers and an internal economist to dwell on some key global and domestic macro data and debate to arrive at the macro call that would influence their investment decisions. The macro analysis is at the market and sector level.

The 2008 global meltdown emphasised the importance of top-down market analysis to view the interplay of economic forces, global risks on stock prices.

Only if one can sniff out such issues early on, can one carefully construct the portfolio to sail through market turbulence.

The top-down analysis may not always get it right, but if the process is followed properly, then the probability of success is high.

Mahesh is on a constant lookout for companies with good management and a key competitive advantage that it has created for itself.

For Mahesh, this gives the company a "right to win" that sector.

***

The systematic investor: Nilesh Shah

Nilesh wanted to make a difference.

"Indians are great savers, but they are lousy investors. There is a whole segment of society which still believes cash is king. They want to keep money in cash. They don't realise that by keeping money in cash, they are losing opportunity and also keeping the country poor."

"If you want to make equity investments, you need to answer just three simple questions. Is this company in a good industry or in a bad industry? Is this company managed by a good promoter or a bad promoter? Is this company available at a good price or bad price?"

"If you can solve this equation and buy companies in a good industry run by a good management at good price, you will always make money."

Nilesh found his lessons in the market due to a different approach. Nilesh's fixed income stint helped him develop a better understanding of promoters and credit.

Having seen promoters who have melted companies, Nilesh cannot but recommend investors to look at the management very, very closely.

"You have to look at his past, and you have to judge his intention in the present to arrive at a conclusion. Experience will make you right, more often than wrong."

"If you are right great, if you are wrong, then cut your positions."

In fixed income, one focuses on not only the ability to pay (which is an analysis of balance sheet and financials) but also willingness to pay (which is the understanding of the promoter).

Nilesh could apply the same knowledge in stock picking, where he looked for parameters like how is the promoter behaving with creditors.

"If a promoter is not behaving well with the creditors, why would he behave well with the shareholders?"

"f a company is not good enough to lend you money, then it is also not good enough to partner via equity investment."

Nilesh avoided many leveraged infrastructure companies by virtue of worry on the promoter background partially driven by the credit background.

Nilesh ran one of the largest infrastructure fund throughout 2006 to 2008, and to a great extent he stayed away from such leveraged companies.

Excerpted with kind permission from the author Anuj Shah and publisher Value Research India Private Ltd.

Please note: The sale proceeds from this book will go to the Pediatric Cancer Department at the Tata Memorial Hospital for treatment of children suffering from cancer.