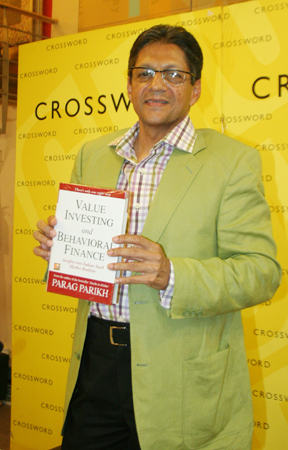

"The financial services industry is a jungle. It's become devoid of ethics. It's all about money, money, money," says Parag Parikh, founder-chairman of Parag Parikh Financial Services. "What was once a profession has become a business. In a profession, you look out for the benefit of your clients. In a business, you see how much money you can make. That's why I wrote this book."

The book is Value Investing and Behavioural Finance: Insights into Indian Stock Market Realities, which Parikh composed primarily at the height of a prolonged bull run, in 2007. As the Sensex touched its highest ever peak of 21,078, he was putting the finishing touches on this sobering, cautious overview of the Indian stock markets.

When the bubble burst, Parikh's countervailing voice suddenly proved prescient. How did he achieve such insight? With the help of ideas he picked up while studying behavioural finance, he says.

It all boils down to this: In theory, investors are supposed to be rational beings that are concerned only with their own interest and act accordingly. So why do investors routinely make irrational decisions that go against their own financial interests?

In Value Investing, Parikh uses behavioural finance ideas, along with practical wisdom learned from decades of experience in the markets, to answer this question.

He spoke to rediff.com about behavioural finance, value investing, the state of Indian stock markets and the opportunities for small investors in today's turbulent financial climate.

You say bonds and other fixed-rate financial instruments are 'riskier' than equity investing. Could you explain this concept, as most people consider the stock market risky and bonds 'safe'?

You have to look at purchasing power. With governments giving stimulus packages and financial bailouts around the world, with all the money being injected into the system, we know that inflation is definitely coming. Proper investing is actually a hedge against inflation.

When you buy stock, you are buying a part of a company. Every one of us would like to own and run our own businesses. But the next best thing is to own a part of a well-run business, one you buy for value, that has good management and a profitable, sustainable business model.

Over time, this method has proven to be the most effective mode of investing in Indian markets. But instead of concentrating on return of capital, we're concerned with other things.

You say that generally, over a long period of time, markets will mirror/reflect the actual economy, but in the short term this is unlikely. Why? Is it the irrationality of investors, linked to psychological traits?

Yes. It is one of the biggest factors in finance. We are all human beings, who are supposed to be rational. We're supposed to look after our best financial interest. But this doesn't happen. We behave irrationally, for a variety of reasons. We all have egos. We're all vain. When we make decisions of the heart, it sometimes goes against our own financial interest. You have to be emotionally strong and emotionally courageous.

Here's a quick example of how investors are irrational: Check the average, typical investor's portfolio. It will have a few winners at the top, followed by a lot of losers. This is a function of our irrationality. Pain is a stronger emotion than pleasure. That explains why people are eager to sell their winners, thus stunting their returns, and too stubborn to sell losers, thus increasing their losses.

We're too stubborn to take ownership of our mistake. We'd rather take more and more risks simply to avoid acknowledging a certain loss.

In investing, failure is predictable, as is success. A strong character separates the winner from the loser. All humans aspire for the same things. Security, comfort, leisure, love, respect and fulfilment. And we all want to get these things as easily and quickly as possible.

What separates good investors from mediocre or bad investors is the ability to delay gratification. The inability to delay gratification is the primary reason for economic failure in life.

It's not only in finance though. It's everywhere. Look at farming, for example. You can not sow your seeds today and harvest your crops tomorrow. Same is true with investing, it takes time.

So, how did behavioral finance and human psychology contribute to the 2008 global financial crisis?

Bull runs and bear runs are natural. It's a cycle. But herd behaviour makes the cycle more dramatic. Herd behaviour explains why some 'buzz stocks' go up very fast, and become overvalued. That's what happened with the market in 2006 and 2007. But the downside is that the same stocks also fall very fast when the same herd comes to sell.

But it wasn't only herd mentality that caused the crisis. There was also a lot of greed. No matter how much you make, you want to make more. Desires always keep growing, because man is never content. This isn't always a bad thing.

But with the financial crisis, so many people forgot they were there to service their clients. People were behaving like barbarians. You see some of these pay packages in the West, hundreds and hundreds of crores (billions) for CEOs of banks. And to justify these packages, people end up behaving irrationally.

All the things done in the market -- these so-called innovations -- are designed to make money for these traders against the interest of investors. It's an unnecessary web of complexity. That's what I wanted to explain with this book. And IPOs are the biggest fraud. Look at the hedge fund managers and all the well-known investors who bought the Reliance Power IPO when it was overpriced. Rather than invest in an unknown value stock, they went along with the crowd, with the well-known company.

That way, if the stock falls, they can say, "Everyone else did it." They're trying to safeguard their own jobs, rather than look after a client's best interest.

And what about after the recently concluded Lok Sabha polls, when trading had to be halted because of such overwhelming positive sentiment? Was that an example of behavioural traits driving the markets upwards? Or is there an argument to be made that stable, coherent governance is necessary for smooth operating of business, and thus investors are right to rush to invest after such a clear mandate has been given?

This is perfect a example of a mental heuristic. It's a shortcut. 'This result of the UPA (United Progressive Alliance) staying in power must automatically mean it's a good time to invest,' we say. These heuristics lead to biases. It's a herd mentality. You try to replicate the success of everyone else, so everyone ends up buying at once.

They say the government is now a stable government, but there are so many other factors besides the election: inflation, financial deficit, unemployment, etc.

If investing is simple, why is there a need for analysts, with all their high-powered spreadsheets and endless monitoring of global stock exchanges?

Analysis of the markets doesn't work. But the jobs of analysts are always safe. The industry is set up so that these jobs are always safe. But you actually don't need to endlessly watch business channels on television, read business newspapers all day, constantly monitor global markets, etc.

I take it easy. Too much information only confuses a true investor. A true investor knows that good opportunities come rarely. If I get one good opportunity a year, I'm happy. Trying to find a 'great deal' every day is foolish.

But the market, the investment banks, the media, some so-called experts -- they're all trying to tell you that these once-in-a-lifetime opportunities come every day. They don't. Investing is inherently a simple concept, but the industry has intentionally made it complicated.

When you look at Warren Buffett, you see a model of consistency and tremendous success, despite this inherent unpredictability of the market. How is he able to maintain such levels of success? What makes an elite investor?

What Warren Buffett famously said is still very true today: When others are greedy, be fearful. When others are fearful, be greedy. That's why Warren has been so successful.

In 2007, when the Sensex was moving toward 20,000, I was turning away business. I didn't feel comfortable investing clients' money in that environment. I was fearful. Everyone was getting carried away. Now, in the last six months, I've never worked so hard in my life, when most other people have been staying away. The last two years are a great example of both sides of Warren's message.

Can you explain your theory that having a high emotional quotient benefits an investor as much if not more than a high intelligence quotient?

In the financial services industry, there are many people with very high IQs. But that doesn't determine success. Success comes from emotional strength. It's called your EQ, which is actually a measure of mental composure.

If you are emotionally courageous and mentally composed, you will have the ability to delay gratification. You must be able to say 'no' to the heart and 'yes' to the brain.

Will you explain your definition of value investing? Why is it preferable?

Value investing is difficult because there's not much day-to-day action. You find an undervalued company in a neglected sector that you think in the long run will beat projections. It takes time.

But a fund manager has to justify his high wages. He has to show why he is worth so much money. So he's always trying to make the quick money. He's speculating on what the stock price will do tomorrow and the day after. In that way, the industry is set-up so that value investing doesn't work. But the results show that value investing definitely provides the best returns when compares to other investing styles.

Will you continue to recommend investors avoid tech stocks, as despite eyeballs they're unable to generate revenue? Is this the classic example of a growth stock?

In 1999-2000, I thought I was going crazy. It was the lowest I've ever felt as an investor. A client would come and ask me about a tech stock. I would look at the fundamentals, and I would see the company just wasn't worth that much. These Internet companies had generated a buzz, and were getting a lot of eyeballs, but they weren't making profits!

The P/E ratios were very, very, very high which goes against my principle of contrarian investing. A high P/E ratio only happens when the investing community is excited about a company or sector. You should be looking for sectors that are at that time unattractive to the community, if you want to be a true value investor. As for the popular tech stocks, I knew they were overvalued. So I would tell the client, "Don't buy this." Two weeks later, the client would come and say, "Good thing I didn't listen to you. The stock price has almost doubled!"

This kept happening over and over again. I got into a depression. I thought either I had gone mad or the world had gone mad. I was telling myself, "I don't understand this new economy. I've lost it. Finance has passed me by."

Then, I took a class on Investment Decisions and Behavioural Finance John F Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. I learned all about the irrationality of investors as a result of behavioural psychology. That's when I said, "A-ha!" The class helped me confirm many of my suspicions. Soon after, the tech bubble burst.

Do you think the Internet will become monetisable any time soon? What sector do you foresee witnessing the next 'bubble', and thus becoming the next growth stocks?

Look, there's no absolute good or bad when you talk about a company -- only good and bad decisions and good and bad stocks. If you bought Wipro in 1994, you made a good decision and it was a good stock. If you bought Wipro in early 2000, it was a bad decision and it was a bad stock.

About so-called growth stocks, there's no such thing. Growth stock investing is based on dreams. I call them 'dream stocks', because you ignore fundamentals and focus on fantasies. You need to judge stocks by basic parameters: valuations, earnings and dividends. When you are paying a huge price for a company with marginal intrinsic value, your returns will suffer in the long run.

What do you feel is the biggest problem or challenge faced by Indian investors today? Have we hit the bottom? Where and what are the biggest opportunities?

The biggest challenge facing the Indian investor is the government managing the fiscal deficit. I believe a stimulus would be dangerous. Stocks would be my best hedge against inflation. I'm worried that hyper-inflation will rear its ugly head. That would be the worst possible thing, hyper-inflation.

Germany has experienced hyper-inflation before, after the First World War. Notice how they are wary of stimulus packages even today.

Any advice for small investors?

Do you feel like the financial services industry has taken a hit in prestige, with the global financial crisis? Why were Indian banks largely able to avoid the massive collapses that characterised the meltdown in the banking sector in the West?

The financial industry will change. It will have to. It's the law of karma. As for Indian banks, only ICICI Bank really took a hit, on those auto loans. But Indians are naturally conservative people, which helped insulate us during the financial crisis. We have a culture of saving.

Americans, and others in the West, have a culture of debt. They buy cars and houses on credit. They take on huge mortgages. They use credit cards. When something goes wrong, the whole system is threatened. It's good a thing that India didn't liberalise the economy entirely. Maybe that's one place where the Left can claim some credit.

If we would have privatised all of our banks, they would have been very fragile. I'm worried that Young India may be starting to imitate the West.

Where do you think India would be today without the markets?

Stock markets are a positive force for the economy. In the Indian context, it allows entrepreneurs access to capital from investors. We can't wish away the market. The market is a good thing. It's about people in the market and how they behave that we have to worry about.