Photographs: Jayanta Dey/Reuters Praveen Bose in New Delhi

Head Held High, which provides training to rural youth and fosters entrepreneurs, is set to break even in 18-24 months.

Accompanied by two of her friends, Chandana T R from Tarabenahalli in Karnataka’s Tumkur district had set out to appear for an interview aimed at selecting youth from backward regions for jobs.

She had just passed her XII standard examinations and was uncertain about what to do next.

Now, she works at the head office of Head Held High Services, which provides employment related training and assistance to entrepreneurs in rural areas.

Before becoming a team leader, she was a data entry operator.

She wants to return to her village and train many others.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

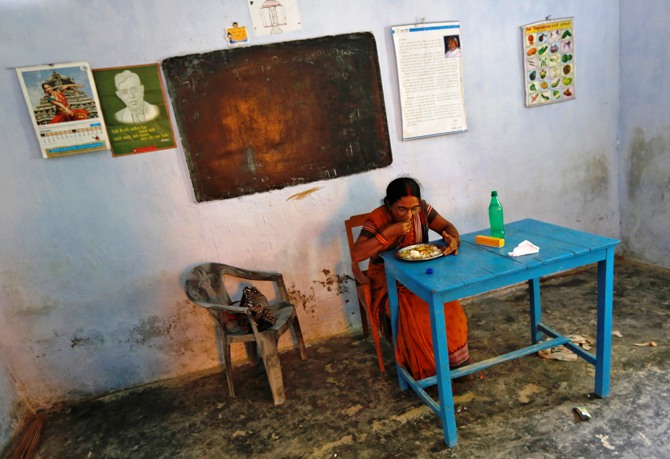

Image: Srimati Kumari, a school headmistress, eats the free mid-day meal, distributed by a government-run primary school, before being served to schoolchildren at Brahimpur village in Chapra district of Bihar.Photographs: Adnan Abidi/Reuters

Chandana is at the forefront of Head Held High’s efforts to set up centres in Tumkur, Gadag, Bidar, Koppal and Hindupur.

Chandana, who hails from a poor family, would now set up her own business, aided by Head Held High.

Markandeyappa from Koppal, a backward district in north Karnataka, worked as a data entry operator after his training.

Now, he is involved in a survey on behalf of Babajob Services, a job portal for semi-skilled workers, for Head Held High. Zakir from Gadag, also part of the project, is an Industrial Training Institute pass-out.

After being trained by Head Held High, he worked with FirstSource.

“The training helped me get a job,” he says.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: Karuna Prakash Mukudum, a coordinator working for Financial Information Network and Operations Ltd (FINO), processes a smart card as she collects money from a woman in Wavanje village of Raigad district.Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

“From being absolutely illiterate, they acquired the ability to converse in English, work on computers and essentially, work like any other employee in a high-tech industry, in less than eight months,” says Rajesh Bhat, co-founder and chief executive of Head Held High Services, which started operations in October 2012.

Co-founder Sunil Savara is managing trustee, Head Held High Foundation.

Early days

Earlier, Bhat was a software engineer at OnMobile, a mobile value-added service company.

In 2007, he set up Head Held High Foundation, joining hands with Madan Padaki (known for his MeritTrac start-up , an assessment company that was later sold to the Manipal group) to develop a concrete plan for the project.

With a dream to change the fate of thousands, Bhat went to villages to understand the needs of the rural youth.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: A labourer rests on harvested wheat crop at Chando village, Punjab.Photographs: Ajay Verma/Reuters

At Head Held High, trainees begin with the basics -- the English alphabet.

They are also familiarised with computers.

Slowly, they begin to understand, read, write and converse in English.

Today, 800 of those the company trained are employed.

HHH is looking to create rural talent and technologies; for this, it aims to be present in every district (not just Karnataka).

India’s huge demographic advantage would be useful if the population is educated and skilled, says Madan Padaki, chairman, Head Held High Services, who joined the company in 2009.

Today, the company has three centres -- in Gadag and Bidar in Karnataka and Hindupur in Andhra Pradesh.

Now, it is considering setting up centres in Chamarajnagar, Tiptur and Hassan in Karnataka. It is also pursuing partnerships across 100 districts.

Padaki terms the rural youth ‘rubans’.

They mirror the urban youth in many ways---talent; entrepreneurship and tech-savviness.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: Women labourers throw dust on a road tarmac under construction at Bharadva village, Gujarat.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

The business

Head Held High has two entities -- Magic Wand Empowerment and Village BPO.

While Magic Wand Empowerment aims to empower the most vulnerable communities through training programmes by providing stable careers through training, Village BPO (business process outsourcing) tries to outsource work to trained rural youth.

Now, it provides a variety of services by leveraging talent and technology.

It has three streams of revenue -- training; revenue earned by providing talent to firms; and its entrepreneur network, through which it builds capacity to market products.

It also runs the Ruban entrepreneur store to market products manufactured by rural entrepreneurs.

These products include eco-friendly products, products for drip irrigation, smokeless stoves, etc.

Head held High also connects these entrepreneurs to the market. Today, it works with about 50 entrepreneurs.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: An operator works on his table while enrolling villagers for the Unique Identification (UID) database system at an enrolment centre at Merta district, Rajasthan.Photographs: Mansi Thapliyal/Reuters

An entrepreneur with a mobile-based system to start a pump needed a distribution base; Head Held High offered to sell it for him. “In two-three years, we will show the model works,” says Bhatt.

To foster rural entrepreneurs, the company launched the Ruban Entrepreneur Network, which started as a pilot in Gadag early this year.

About 50 joined the network; they attend meetings once a month, including training sessions.

Youth with potential are encouraged to start their own businesses, with product linkages, financial assistance and personalised mentoring through RubanHubs.

Rural BPO operations are now on the RubanSource platform, which aggregates demand for services offered by the BPO.

These services include marketing of products sold by entrepreneurs (through the BPO) and assistance to its Rural BPO members to deliver quality services.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: Village women labourers work at the construction site of a road at Merta district, Rajasthan.Photographs: Mansi Thapliyal/Reuters

“The model of rural development has to have an impact; it has to be sustainable and rapidly scalable, and we believe we have found such a model in RubanHubs,” says Padaki.

The company plans to train two million in 10 years.

It is now extending its training model to six additional districts, with an aim to increase the number to 100 districts in 18-24 months.

“I believe enterprise growth has to happen from the rural end.

“The subsidies platform is endless,” says Padaki.

He hopes the company’s work would help it become a part of the National Skills Development Corporation’s skill training programme.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: A farmer shouts while controlling his pair of oxen as they race through a paddy field during the 'Kakkoor Kalavayal' festival at Kakkoor village, on the outskirts of Kochi, Kerala.Photographs: Sivaram V/Reuters

Finances

The training fee of Rs 25,000 is paid by the youth.

At times, they also part-pay it, with the remaining amount accounted for by loans to the youth from Head Held High.

The loans are later repaid in instalments, after the youth secure jobs.

“This makes them serious about the training,” says Bhat.

Recently, the company raised Rs 2.5 crore (Rs 25 million) from investors.

It hopes to raise Rs 15-20 crore (Rs 150-200 million) by the end of this year.

In two-three years, years, it hopes the capital base would be raised to Rs 100 crore (Rs 1 billion).

In 2012-13, the company earned revenues of about Rs 50 lakh (Rs 5 million); estimated revenues for 2013-14 stands at Rs 2 crore (Rs 20 million), while that for 2014-15 is about Rs 8 crore (Rs 80 million).

The company is set to break even in the next 18-24 months.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: A farmer collects betel leaves near POSCO India's Odisha Project site at Gobindpur village in Jagatsinghpur district, Odisha.Photographs: Reuters

Angel investors of Intellecap Impact Investment Network and Unilazer Ventures, among others, have invested Rs 2.5 crore (Rs 25 million) in the company through the last round of funding.

While the company is showing scale, it’s not exactly a high-return business. For private equity funds, a caveat is Head Held High is not a ‘get-rich-quick’ model.

It’s an 11-12-year game, says Padaki.

“We may not give five times or 21 times returns; and, if you want the internal rate of revenue to be 30 per cent, I am not the guy,” he adds.

The company’s internal rate of revenue is a muted 18 per cent.

Investor speak

Recently, Ronnie Screwvala’s Unilazer Ventures had invested in the company; it wants to be an impact investor.

“We saw the realities on skill levels at the ground level.

“One of the key challenges was creating rural employment in recently-skilled arenas,” said Amit Banka, managing director, Unilazer, adding, “We wanted to tie up the skill-development part and take it to a logical end in rural and semi-urban areas. . .

Also, the company had an interesting thought process,” he said.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: Village woman Kiran Mallick, 53, who works at a road construction site under National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in West Bengal.Photographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

An angel investor in Head Held High told Business Standard he wasn’t in a hurry to exit. This sector is not one in which an investor can look at an exit in five-seven years; it’s long-term play.

Risks

The company provides residential training and, as well as food, for the youth.

And, it facilitates loans; repayments are recorded from the ninth month.

One can repay through equated monthly instalment of Rs 1,000.

“Head Held High assumes the risk of defaults; if a person defaults, the liability is on us,” says Padaki.

The company hopes to have 10,000 trainees.

Many have dismissed the company’s model as unworkable. The company is bent on proving otherwise.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: A worker pushes a trolley inside a nylon yarn manufacturing factory at Palsana village on the outskirts of Surat, Gujarat.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

EXPERT TAKE

The concept, tool and methodology of Head Held High is relevant, appropriate and the call of the hour.

Learning through conversations is certainly addressing the challenges faced by the poor youth in rural and remote regions.

The methodology also addresses the fear of alienness.

Though in a small scale, the outcome, at individual, family and community levels, is quantifiable and sustainable.

The model is sustainable, scalable and replicable.

This initiative deserves support to create a pool of young minds that would be active, value-creating and responsible.

The image is used for representational purpose only

. . .

How to make rural India job-ready

Image: Supporters of India's ruling Congress party listen to a speech by party chief Sonia Gandhi during an election campaign rally.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

The management team, headed by Sunil Savara, Madan Padaki and Rajesh Bhat, is not only committed, sincere and passionate, but also a rare combination with strong minds, social hearts and a vision of at least two decades.

But the model faces some challenges and problems.

How would they be able to scale up?

Also, if English is done away with from schools, how would they manage?

A major issue is getting enough quality instructors, as they start to scale up. Another issue is of accents.

Would they bring in uniformity?

As they go pan-India, this could prove a hurdle.

Mukti Mishra is chairman of Gram Tarang Group, which imparts skill training in rural areas of Odisha.

The image is used for representational purpose only

article