| « Back to article | Print this article |

Are we living through a period of unprecedented corruption? This is a common, casual assertion, for which I have seen no sensible evidence either confirmatory or contradictory. But, if it's true, there could be several explanations.

Let us suppose that it is indeed the case that corruption is not merely more visible thanks to a noisier media and the Right to Information. Some argue it's a breakdown in public virtue. Really? The India of the 1980s was somehow less venal?

That's viewing the past through hopelessly rose-tinted glasses. Or is there something in the DNA of India's development project that's causing this perception?

To many, the answer lies in the increasing role of the private sector. Consider for a moment the Comptroller and Auditor General's (CAG's) report on coal allocations. Could such a report have been written, say, 30 years ago? Perhaps not.

Yet, as anyone who has seen Gangs of Wasseypur or listened to Sneha Khanwalkar's lazy voice in "Coal Bazaari" over a backbeat of miners' pickaxes will tell you, it isn't as if the coal sector wasn't venal back then, or that people weren't making illicit money.

No; it is that the private sector's participation in a dirty business was finally given structure by the allocation of captive mines - and thus the auditors could move in and tut-tut grandly.

Indeed, pause for a moment and consider how changed is the nature of the corruption about which we worry. It's no longer about arms deals or big government procurement or diverting public funds; it's about underpriced resources, or excessive compensation for doing jobs earlier associated with the state.

The concessionaire at Delhi airport gets "too much" real estate. Power companies make windfall gains because they're given coal mines. Some companies are picked to get cheap telecom spectrum. Everywhere, partnerships between the public and private sectors seem to be the source of corruption. Clearly something has gone very wrong.

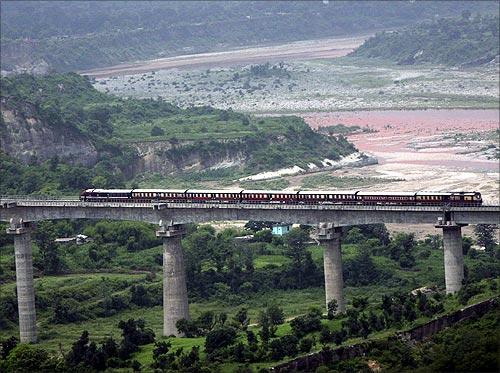

It has been known and argued by four governments under three different dispensations the UPA, the NDA and the United Front that private investment in infrastructure, in partnership with the government, is essential.

Over the past 10 years, this involvement has been scaled up dramatically, the source first of India's world-beating growth and now its growth-choking, tail-swallowing fear of corruption.

The government originally estimated that 11th Plan investment in infrastructure, between 2007 and 2012, would be $320 billion in 2005-06 prices. At the beginning of the period, the World Bank estimated that 20 per cent would come from public-private partnerships, or PPPs.

Eventually, it looks like the PPP composition was about around 37 per cent of $500 billion (the telecom sector accounted for much of the difference in total spending). And, for the 12th Plan, the government intends it to be 50 per cent of $1 trillion.

Yet it seems odd that, even as the lack of public funding is being given as a reason for PPPs, the share of government financing hasn't come down as much as you'd think. Indeed, according to a study from PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), in 2002 the degree to which the average PPP was funded by the project developer went down dramatically.

The Planning Commission's figures show the share of public finance in infrastructure in 2007-08 was 65 per cent; in 2011-12, it was 60 per cent, giving you that final 37 per cent figure for the five-year period as a whole.

In the first three years, equity financing, indicating investor participation, was only around 14 per cent; of the debt financing, commercial banks (including public sector banks) were only 21 per cent. Yet another failure of India's financial system: India's ordinary investors aren't paying for its infrastructure.

Thus, investors who enter this sector aren't normal people. They have to have a high appetite for risk political and regulatory or an ability to "manage" it.

Unsurprisingly, they want super-sized returns. In 2006 PwC also conducted a survey of the returns to their equity that most investors expected. Seventy-three per cent of them said: "over 16 per cent." PwC pointed out that this excluded, even, the money that they expected to make by handing their own divisions construction contracts for the project they'd won.

We're getting people to build our infrastructure, therefore, who are looking for the big money. But revenue from infrastructure never pans out like that. Thus, they put in tiny amounts of equity, leverage their political connections, and then make money by changing terms afterwards, or by selling their equity at a massive premium once the government's requirements have been "managed".

You've got to wonder about the quality of the assets they're building. Delhi's airport metro had to close shop because of safety concerns. The private developer, Reliance Infra, is also involved in the Mumbai metro project, a pillar for which collapsed spectacularly last week.

On the other hand, cost can't be the paramount consideration either, as so many do-gooders from the CAG downwards would like. Remember the astronaut Alan Shepard's famous line about Nasa: "It's a sobering feeling to be up in space and realise that one's safety factor was determined by the lowest bidder."

Sadly, private sector involvement in infrastructure has become, in effect, private sector involvement in resource extraction. Power becomes coal. Telecom becomes spectrum. Highways become land. Steel becomes iron ore.

Wherever in the world, whenever in history, the private sector has been allowed to dominate resource extraction, there's been trouble. Oligarchies have formed - and Reliance Industries' ability to bring South India to its knees by denying gas to power plants shows the danger of that, surely.

Workers and locals have been exploited; or destabilising clashes have built up between foreign investors and domestic interests. Resource extraction and pricing need a firm state hand, and the incapacity of the Indian state is not a reason to ignore that fact.

China can overinvest in public infrastructure because it controls its entire financial system.

India doesn't have that luxury. But, at the very least, it needs to beef up state capacity: to build, to operate - and, if private capital is still desired, to regulate. PPP cells at the Centre and the states, which the Asian Development Bank set up, are woefully inadequate.

The prime minister and the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission are both fans of PPP investment; but they have been equally outspoken about fixing regulation.

There should be no further delays in introducing the draft regulatory reform Bill. And the national PPP policy announced last year should be used as a basis for a PPP Act that plugs the many loopholes in sectoral regulation.

The Supreme Court and the CAG aren't competent to do this job. But the government can't seem to draft decent contracts or bid terms either. Nor do retired bureaucrats make the best regulators.

Here's one idea some are tossing around: if you set a thief to catch a thief, set the private sector to catch the private sector. Private sector expertise shouldn't be ignored in drafting and monitoring infrastructure contracts.