| « Back to article | Print this article |

Modi's unexpected announcement of achieving net zero by 2070 may have neatly deflected the pressures on India to sign up to an ambitious pledge but it does nothing to dispel the ecological emergency that threatens all life on the planet, points out former forerign secretary Shyam Saran, the prime minister's special envoy and chief negotiator on climate change 2007-2010.

Before assessing the significance of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's five-point Panchamrita pledge at Glasgow, some key elements in the current discourse on climate change should be clarified.

Countries are being asked to sign on to a net zero emissions target by 2050.

The term 'net zero emissions' is a balance sheet concept.

Global emissions need not fall to zero by 2050.

They could conceivably keep rising as long as enough negative emissions in the shape of 'carbon sinks' are somehow rolled out to exactly balance the plus side of the balance sheet.

Nature provides carbon sinks through forests and the oceans, including marine and coastal vegetation.

There may be as yet unviable and untested but technologically feasible fixes, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and geo-engineering solutions.

For the foreseeable future, it is only by expanding the absorptive capacity of natural sinks that negative emissions may increase but the scale required by 2050 may be problematical.

Let us turn to another multilateral event which took place at Kunming in mid-October this year, the Conference of Parties to the Biodiversity Convention.

This turned the spotlight on the rapid rate at which the world's forests are being depleted through logging, forest fires and environmental degradation.

The oceans are awash with vast islands of floating plastics while the dumping of hazardous wastes is turning many deltaic regions into dead zones where no marine life is possible anymore.

Thanks to ocean pollution and to already rising temperatures, ocean chemistry is changing with less capacity to absorb carbon emissions.

It is estimated that these natural sinks together absorb some three quarters of global carbon emissions but this capacity is getting relentlessly eroded.

Climate change and biodiversity are two sides of the same coin.

You cannot continue to destroy the planet's biodiversity and hope to tackle climate change.

None of the proposed technological fixes have had any encouraging results so far.

The CCS has been around for nearly two decades but there is not a single major coal-based thermal plant actually fitted with this technology.

If a 1000-MW thermal plant costs $1 billion, its CCS installation would cost another billion.

The economics simply does not work. PM Modi's unexpected announcement of achieving net zero by 2070 may have neatly deflected the pressures on India to sign up to an ambitious pledge but it does nothing to dispel the ecological emergency that threatens all life on the planet.

Since China's President Xi Jinping was not physically present at Glasgow, PM Modi took centre-stage on several occasions, engaging in friendly banter with several important leaders and this plays well domestically.

Given the huge difference in their levels of emissions, India achieving net zero only 10 years after China's declared target date sounds eminently fair and reasonable, even more ambitious by contrast.

However, 2070 -- and even 2050 -- is very far into the future, given the accelerating technology driven change that is sweeping across the world.

We have a new data-driven digital world, with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, which techno-optimists believe will deliver solutions to the climate crisis before doomsday strikes.

This is a dangerous bet.

Countries have now made pledges to reduce methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 and to begin to reverse deforestation by the same year.

Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas but contributes much more to warming than carbon dioxide.

But it is the steadily melting perma-forests of Greenland and Siberia which may lead to a huge and dangerous upsurge in methane lying locked up in frozen vegetation under the ice.

As for reversing deforestation, there is unlikely to be any progress as long as a tree cut down for sale as timber has more marketable value than a tree growing in the forest.

It is in this context that the rest of the four amrita tattvas or sources of nectar announced by PM Modi are much more near-term, significant and substantial.

He has pledged that by 2030, India's non-fossil energy will be 500 gigawatts (GW) as against the earlier target of 450 GW.

Thanks to this push towards renewable and clean energy, a billion tonnes of carbon emissions will be reduced between now and 2030 against a business-as-usual trajectory.

The carbon intensity of gross domestic product growth will come down by 45 per cent by 2030 against an earlier target of 33-35 per cent announced at Paris.

PM Modi also announced that by 2030, 50 per cent of India's energy would come from non-fossil sources.

The foreign secretary later clarified that the PM was referring to installed electricity generation capacity by that date.

This was earlier set at 40 per cent. However, this means that for the foreseeable future coal will continue to be the mainstay of power production.

Taken together, these pledges certainly represent enhanced ambition and put the spotlight back on the advanced and affluent countries that still evade their responsibility and continue to shift the burden of energy transition on to the developing world.

PM Modi was right in demanding climate justice and that the developed world step up to the plate in providing much higher levels of finance and technology to enable climate change action by developing countries.

He mentioned a figure of $1 trillion but did not indicate the time span over which it should be disbursed.

The International Solar Alliance, which was an Indian initiative at Paris in 2015, has not made much progress so far.

An initiative first announced in 2018, the One Sun One Grid One World project has been given a push through partnering with the UK, which has its own but related Green Grid project.

But the challenge of creating a common cross-border grid even regionally is daunting, let alone a global network.

Under the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure, PM Modi announced the Infrastructure for Resilient Island States initiative, taking into account the greater frequency of extreme climate events that have affected the most vulnerable parts of the world.

Financing will remain the main challenge. Neither may gain immediate traction but help burnish India's green credentials.

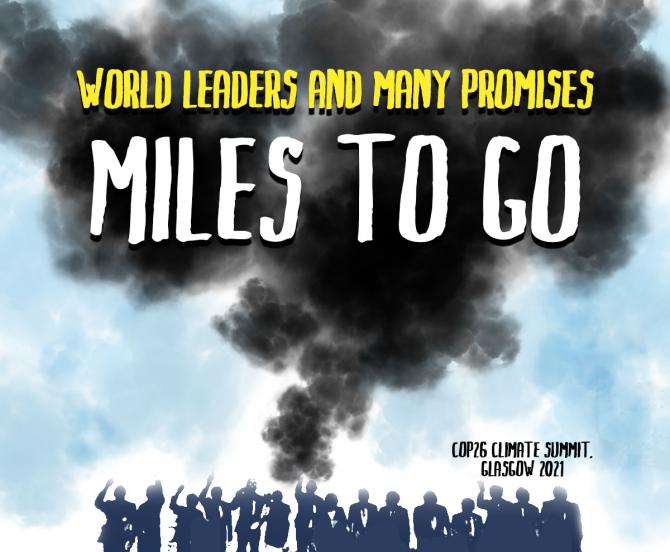

How should one describe India's Climate diplomacy at Glasgow? A modest but welcome green shoot in a gathering high in decibels but low on substance.

Shyam Saran is a former foreign secretary and a senior fellow, Centre for Policy Research. He was the prime minister's special envoy and chief negotiator on climate change 2007-2010.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com