| « Back to article | Print this article |

Amendments to the Child Labour Act say children can work in ‘family enterprises’ but the definition isn’t clear, points out Shyamal Majumdar.

Amendments to the Child Labour Act say children can work in ‘family enterprises’ but the definition isn’t clear, points out Shyamal Majumdar.

Varun Gandhi may have gone overboard when he described the amendments to the Child Labour Act as “lunacy”, but some of the provisions in the Bill, which was passed by the Lok Sabha last month, raises questions about who the targeted beneficiaries are.

On the face of it, the amended legislation has done all the right things - it has banned employment of children under the age of 14 across all sectors, prohibited employing those aged between 14 and 18 in “hazardous occupations”, and introduced stringent fines and jail terms for offenders. But the devil lies in the details.

For example, the new law has slashed the list of hazardous occupations from 83 in the previous law to three - mining, inflammable substances and hazardous processes, as defined in the Factories Act.

It’s true the definition of hazardous industries in the earlier law that came into effect 30 years ago needed to be reviewed, but wielding an axe was certainly not the solution.

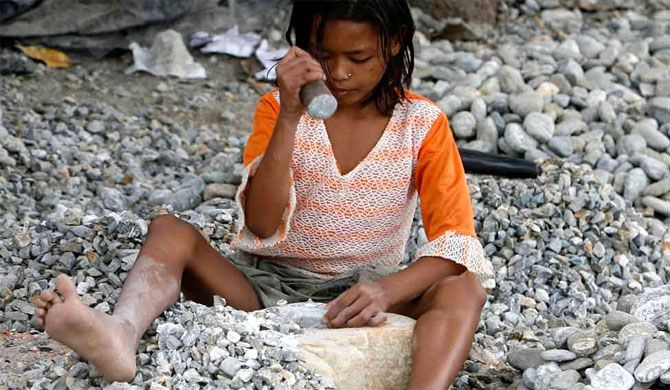

Take stone crushing. An ANI report on the stone quarries in West Bengal’s Siliguri district talks about hundreds of children spending eight hours a day by the riverside, fishing out stones and breaking them into gravel with hand tools twice the size of their tiny hands.

The constant hammering means blistered hands and feet and prolonged exposure to fine limestone dust leaves many with life-threatening respiratory disorders. Employed through contract companies, they lose a sizeable chunk of their money to middlemen.

Another example is of a slaughter house in Parbhani, a small town in Maharashtra. Over half of the workers at the slaughter house were children and had to cut, skin and break the bones of the cattle. Some had to even blow into the spleen of the dead cattle. It’s not clear whether the new definition of hazardous industries covers stone quarrying and slaughter houses.

But the worst part of the new legislation is the clause that children up to the age of 14 can be employed in “family enterprises” outside school hours and during vacations. This is a big loophole as it is unclear how the family is defined, and whether this extends to working for other relatives.

As Bachpan Bachao Andolan founder and Nobel Peace prize winner Kailash Satyarthi has pointed out, between January 2010 and December 2014, his organisation rescued 5,254 children from situations of exploitative labour and more than a fifth of them below 14 years were employed with “family” members.

Besides, in a “family enterprise”, who makes sure that the child is not working during school hours? Bachpan Bachao Andolan found about a third of children were found marked present in schools in their villages in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, on the same day they were rescued from zari-making, carpet stitching units in New Delhi.

Understanding Children’s Work, a report published by the United Nations, states that if combined, both work and education, quality and learning outcome will suffer. Unicef has said that under the new child labour law, some forms of child labour may become invisible and the most vulnerable and marginalised children may end up with irregular school attendance and could be forced to drop out of school.

Besides, work that is conducted within the family or at home is often harmful to children, such as working in cotton fields and other farming activities, and carpet weaving and metalwork.

The other concern is poor implementation of laws in a country, which is home to the world’s largest number of child labourers (the official estimate is 11 million though the actual figure is more than 75 million).

Since 1933, there have been laws in force that ban or regulate child labour, including Article 24 of the Constitution that expressly prohibits it. None of these provisions has been effective in curtailing its proliferation.

A survey conducted by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights showed that hundreds of children were employed in illegal mining of mica in Jharkhand and Bihar. Lakhs of children still continue to work in firecracker and matchstick factories or are involved in carpet weaving, embroidery or stitching footballs in wretched conditions.

That legislation can have only a negligible impact is apparent from the fact that child labour is nothing but a by-product of grinding poverty.

Photographs: Damir Sagolj/Reuters and Andrew Biraj/Reuters