| « Back to article | Print this article |

'My steamy weekend affair'

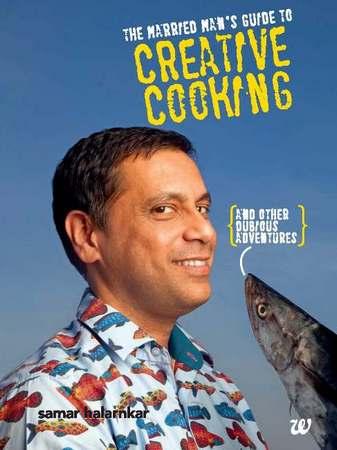

An exclusive excerpt from Samar Halarnkar's The Married Man's Guide to Creative Cooking And Other Dubious Adventures.

Samar Halarnkar cooks and writes. He is the former managing editor of Hindustan Times and has been a journalist for 23 years. Halrankar lives in Bengaluru and has authored Nirvana under the Rain Tree, an early chronicle of India's Internet revolution.

In his new book The Married Man's Guide to Creative Cooking And Other Dubious Adventures, Halarnkar makes a strong case for why men need to cook. He also tells you how you can get your sons to step into the kitchen early. And how easy it is to shop, chop, baste, marinate, saute and stir.

We bring you an excerpt from the chapter titled 'My Steamy Weekend Affair' with the kind permission of Westland Books

My Steamy Weekend Affair

How I learned about the thing that cannot be rushed

We fell in love on a warm monsoon weekend, nearly thirteen years ago. I can't forget those furtive touches, spice-laden caresses and the grand finale that steamed up my glasses.

Down, all of you.

That's what the ancient Indian art of dum or sealed steam-cooking does to me. My friends always did question the ecstasies that food sparked in me, but their fears that I would spend my life divided between writing and the kitchen dissolved when a woman wriggled her way into my attentions.

Still, dum cooking and I brook no distraction. When I put something on dum, my eyes tend to glaze over as I spend my time tending to the details and getting excited about the possibilities.

I've always attempted dum cooking on a weekend, when I have time on my hands: this is not something that should be rushed. Dum is the ancient Indian method of steaming or stewing food in its own juices -- mmm, doesn't that sound exciting already? -- in a vessel or pan, sealed with dough. You can also use foil instead of a cover and then seal it with dough.

The purists will tell you that you need to use a spherical clay pot, a handi. That would be ideal. But I've never gone beyond a battered aluminium pan and a worn non-stick vessel.

It works.

Dum is particularly good when you're having guests because (a) it's an easy method to cook for many and (b) it looks cool, doesn't it, to cut through the dough and let them inhale that flavour-laden steam.

There's a reason the Mughal Empire was so taken with dum cooking. More than looking regal, it is the best way to retain the flavours of meats and spices.

I don't really have a favourite dum recipe. You can throw in any combination of spices and meats -- don't try fish unless you want a soupy mess.

As you would know by now, I am a firm believer in experiments in the kitchen. Thirteen years ago, when I first tried my version of dum cooking, it worked immediately. I do remember though, that the gravy was watery, possibly because I had not dried the chicken well.

The recipe I'm offering you later on in the chapter is my version of something I read somewhere as a Kashmiri Pandit dish. Of course, the Pandits never used olive oil or rosemary.

My colleague Ashutosh Sapru tells me Pandits never even cooked chicken, mostly -- like their Muslim cousins -- mutton and fish. Chicken was first cooked in his home only in the 1980s.

Till the day she died, his grandmother refused to eat it.

There are other ways of steaming that don't involve the Indian dum, of course.

It all began seven years ago, when I was giving my in-laws a really hard time.

They were going to the US -- as they often do to meet their son -- and asked what they should get me.

'A bamboo steamer,' I said, prompted no doubt by some dumplings I'd had (I don't really remember) recently. A steamer, if you don't know, is that exotic wooden thingy they produce with a flourish at Chinese restaurants, usually to serve fragrant dumpling, spare ribs, steamed squid and other delightfully delicious (and ultra healthy) delicacies.

This was not a kind thing to do.

The vexatious bamboo steamer was not available at those faceless, sprawling American malls. Several days, awkward inquiries and false leads later, they found a bamboo steamer in Seattle's Chinatown. It was carefully packed and taken on a transcontinental flight to India.

My in-laws, obviously, found it hard to forget the bamboo steamer. I am ashamed to say I forgot about the contraption, after the initial rapture of receiving it.

Three years ago, I was idly watching the water for tea boil one steamy, summer morning -- this is just so you know I make tea for my wife, come rain or storm -- when I realised I was being a fool.

My excuse for not using the steamer all these years was that I couldn't find the right vessel. You see, a steamer is powered by, well, very hot steam, which floats through its slatted bottom. The heat from the steam cooks the food. You can do this with next to no oil.

The other excuse was just that, an excuse: what do I know about steaming? But for someone who's freely experimented in the kitchen, this was a wimpy excuse.

So, as the water boiled, I quickly rummaged through the kitchen shelves and there it was, forgotten and forlorn all these years.

The steamer.

The lid was a little ill-fitting -- warped no doubt by years of storage, the wood expanding and contracting through winters and summers.

That night, I put it to use, steaming five pieces of surmai (kingfish) with a light marination of sesame oil, soy sauce, lime juice and pepper.

I am happy to report it was delicious. Nothing could be easier. It took all of ten minutes after the water started boiling.

The great thing about steaming is you can do something different each time. You can use a variety of spices, fresh herbs, sauces, anything really. Just remember that heavy Indian spices -- like garam masala -- are not a good idea because these need to be fried.

Of course, you will need to get a steamer, which I hear you can in Mumbai, Delhi (try the Gurgaon malls) and perhaps Bangalore. If you don't have a steamer, you can simply place a wire mesh over a boiling pot of water, cover it with a lid and, presto, a steamer. It's just that bamboo steamers impart a delicate, woody fragrance to the food.

While we are on the topic of steaming, let me tell you the strange tale of Pangasius hypophthalmus -- in a paragraph.

For centuries, this strange creature kept to itself in the riverine depths of south-western Vietnam. Then, the trade engine of the flattened world of the twenty-first century dragged it out of the Mekong river delta, plonked it in a fish farm and passed it off as something it is not. Via Kolkata, it finally wound up in my New Delhi kitchen, where, in a bamboo steamer imported from Chinatown in the North American city of Seattle, it became my lunch.

If this isn't globalisation, I don't know what is.

My personal discovery of the Pangasiidae family began in early 2011 in a restaurant where for the first time I ate an expertly done pepper-encrusted basa -- crisp and firm on the outside, soft and flaky on the inside.

'My steamy weekend affair'

For those of you who are as ignorant as I was then, the most well-known member of this family is the basa, a delicate, light fish with flaky, white flesh. In one remarkable decade, the basa has become -- globally, and now in India as well -- the fish of choice for fillets. Vietnam controls more than ninety-nine per cent of the basa trade, most of it farmed to keep pace with skyrocketing demand.

Now, if you have read the first few chapters of this book, you will know I come from a family that abhors river fish and shuns fillets. But, alas, in these rushed times, balancing profession with parenting, I succumb frequently to the lure of a phone call to the fishmonger who does home delivery -- and since this is Delhi, populated by Punjabis who don't really know their fish, he offers only fillets.

One day, my mysterious fishmonger -- he's only a voice at the end of a phone line -- offered me basa. The same, exotic basa that I ate at fancy restaurants? Well, at Rs 350 per kg, it wasn't very cheap, but these were fillets and my fish of choice, surmai (kingfish) and pomfret, with bones, often cost as much.

Since then, I confess, I have bought basa often -- or at least what I thought was basa.

When I started work on this book, I took, for the first time, a closer look at the label on the sealed plastic packet that holds the basa. I realised I was being fooled, as perhaps were many Indian consumers.

My suspicions began with the brand name on the packet. It said, 'IFB Basa', with the 'IFB' font hijacked from the distinctive 'IFB' of the washing machine company.

The 'IFB' on my fish referred to IFB Agro Industries Ltd of the East Kolkata Township, the importers, who sourced the fish from Long Xuyen town in Vietnam's An Giang Province. The label said: Best before November 4, 2012.

The long shelf life isn't surprising: basa stays well and when unfrozen feels very fresh indeed. But here was the rub. In grand fashion, the label said the basa's name was Pangasius hypophthalmus. Well, well. A little research revealed that the fish I had was from the same family as the basa but wasn't actually basa. The basa is Pangasius bocourti, an iridescent shark that isn't a shark at all but a catfish. My fake basa is also a shark catfish, and since I am now not sure if I've been eating the right family member, I don't really mind being fooled.

I turned my attention to cooking the fake basa. I didn't think dunking it in Goan curries or frying it, as I have done before, was a great idea. Long-lasting yet delicate, basa and its cousins appear to demand more creativity, a lighter touch, as it were.

So, I rummaged through my unused-kitchen-implements shelf and dragged out that magnificent bamboo steamer. What could impart a lighter touch to my Vietnamese friend than steaming?

My experiments with the fake basa are detailed at the end of the chapter. I am happy to report they were successful. I think the key to cooking shark catfish is to use the minimum possible spices and not smother them, as we tend to do. I am sure the real, river basa tastes even better, but to me, the fake worked well enough.

Postscript: A reader of my blog gently pointed out that while I was right about the fake basa, the trademark of the company that sold it was not fake. IFB Agro Industries is an offshoot of the same washing-machine company. This, after all, is the age of opportunity, and trust an Indian washing-machine company to explore real opportunities in a fish with faked origins.

Cooking note: The three basa recipes involve steaming. Steaming time depends on the thickness of the fish. A piece of fish weighing 100-150 gms about half an inch thick should take no more than fifteen minutes. I used a bamboo steamer (sitting atop a steel vessel of boiling water). You can steam in anything with perforations, like a sieve, or a rice cooker. Wrap individual pieces in banana leaves; you can also wrap in foil and bake. I steamed all three fish pieces together. They are very light and will barely serve two people.

Steamed fish in banana leaf (serves 2)

Ingredients

- 2 medium-sized mackerels, or two large steaks of surmai, or a small pomfret, or four fillets of any firm fish, with slits on the sides

- Banana leaf or butter

- paper to wrap fish

- 2 tbsp ginger or galangal

- (Thai ginger) juliennes

- 2 tbsp spring onion stalks

- (from just above the bulb), sliced diagonally

- 6-7 kaffir lime leaves

- 1 tbsp basil leaves

- Salt to taste

Marinade

- 1 tsp sesame (or olive) oil

- 1-2 tbsp soy sauce

- Juice of 1 large lime

- Fresh ground

- black pepper

- Paprika or red chilli

- powder to taste (optional)

Method

- Wash the fish and drain all water.

- Mix all the marinade ingredients. If you want a little spice, it's a good idea to add some paprika or red chilli powder to the marinade. Apply it to the fish, rubbing into the slits.

- Clean and cut a banana leaf or butter paper to line the bottom of the steamer. Place the fish pieces next to one another on the leaf. Sprinkle the fish with ginger, spring onion, kaffir lime leaves and basil.

- Heat lots of water (fill to just below the brim) in a vessel that is largely the same size as the steamer. Make sure the steamer bottom and the vessel rim are a good fit.

- When the water is boiling briskly, place the steamer on top and close the lid.

- Watch the clock. Your fish will be ready in 10 minutes. Serve hot.

Note: If the ingredients I used sound complicated, do it Indian style and marinate the fish in a little oil, red chilli powder, tamarind water (or lime juice) and a little turmeric powder.

Kashmiri Dum Chicken with Rosemary (Serves 4-5)

Ingredients

- 1 kg chicken

- 1 tbsp olive oil

Marinade

- 1 heaped tsp dried ginger

- (saunth) powder

- 3 heaped tsp fennel

- (saunf) powder

- 2 tsp red deghi chilli

- powder

- 1½ cups curd

- Salt to taste

- A few saffron strands

- 15 seedless raisins (kishmish)

Sealing dough

- 2 cups wholewheat flour (atta)

- ½ cup water

- Garnish

- 3 sprigs of rosemary

Method

- Wash and clean the chicken. Drain all water.

- Mix all the marinade ingredients well and rub into the chicken. Set aside for at least 1 hour (5-6 is best).

- Roughly prepare a chapatti dough with the flour and water. Roll out into 2-3 baton-sized noodles.

- Heat the olive oil in a medium non-stick pan. Don't let the oil smoke. When hot, add the marinated chicken. Increase heat and turn over for 5-10 minutes.

- Reduce heat to the lowest and place the pan on a tava or griddle, so it does not get direct heat. Close lid and start sealing, taking care to press the dough down on the lid and the sides of the pan. Take care, the pan will be hot.

- Allow the chicken to steam in its own juices for about 70 minutes. Patch up the seal with dough if you spot leaks.

- With a knife, cut open the seal. Sprinkle with rosemary. Serve hot with accompanying raita (page 177). Best with plain, steamed rice.

- Option: Sprinkle home-made garam masala powder after opening seal. Pound or grind the seeds of 2 black cardamoms (badi elaichi), 1" cinnamon (dalchini) stick, 7-8 cloves (laung), 9-10 black peppercorns.

Excerpted with the kind permission of the publisher Westland Books. Rs 495