| « Back to article | Print this article |

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

Over the past three decades, as developing economies industrialised and began to compete in world markets, a global labour market started taking shape, says McKinsey Global Institute in a report.

As more than one billion people entered the labour force, a massive movement from "farm to factory" sharply accelerated growth of productivity and per capita GDP in China and other traditionally rural nations, helping to bring hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.

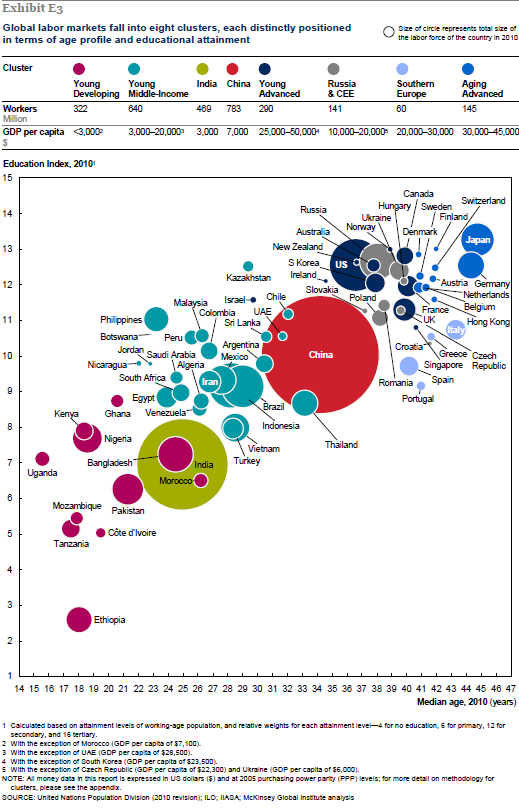

To raise productivity, developed economies invested in labour-saving technologies and tapped global sources of low-cost labour. To understand the issues, McKinsey Global Institute looked at 70 countries that account for 96 per cent of global GDP and are home to 87 per cent of the world's population.

By plotting their populations' educational and age profiles, as well as per capita GDP, MGI sees how prepared their national labour forces are to meet future demand, how easily they can grow their labour forces, and how productive their labour is.

Let's have a detailed look at McKinsey's report.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

In this report by the McKinsey Global Institute, it identifies forces of demand and supply that are shaping a global labour force that will grow to 3.5 billion by 2030.

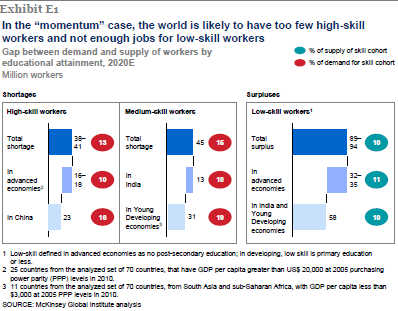

It documents these shifts and analyse the implications for workers, national economies, and businesses. It concludes that the forces that have caused imbalances in advanced economies in recent years will grow stronger and that similar mismatches between the skills that workers can offer and what employers need will appear in developing economies, too.

If these trends persist - and absent a massive global effort to improve worker skills, they are likely to do so - there will be far too few workers with the advanced skills needed to drive a high-productivity economy and far too few job opportunities for low-skill workers.

Developing economies could have too few medium-skill workers to fuel further growth of labour-intensive sectors and far too many workers who lack the education and training to escape low productivity, low-income work.

These potential imbalances are based on our "momentum" case, which uses current patterns in demographics and in the demand and supply of labour to project likely outcomes in the next two decades.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

With large and rapidly growing populations and increasing access to global markets, developing economies became the world's largest suppliers of low-skill labour.

These workers filled rising domestic needs as their countries industrialised and helped meet demand from the global economy, too.

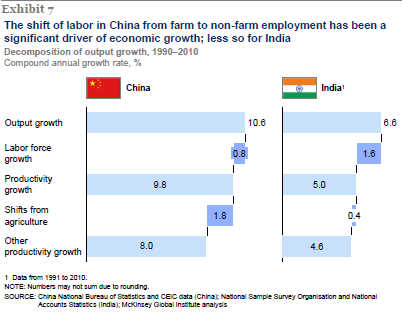

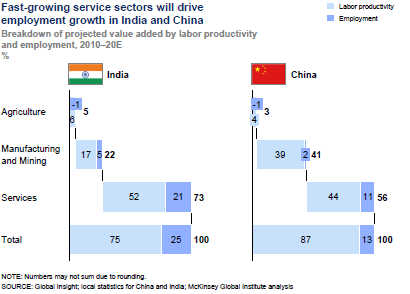

China added 121 million non-farm jobs in its expanding manufacturing and service sectors in the past decade; more than 80 million of these were filled by workers shifting out of low-productivity agriculture, helping accelerate productivity

gains.

About 33 million jobs were created in manufacturing, and about a third of all new non-farm jobs were associated with exporting industries. China's focus, since the 1950s and 1960s, on educating both rural and urban workers across the nation, was reflected in the secondary education attainment rate of 60 per cent in 2010.

The result has been a dramatic increase in per capita GDP, which rose to 20 per cent of advanced economy levels in 2010, from three per cent in 1980.

India followed a similar path, but at a slower pace. In the 2000-10 decade, for example, India created just 67 million non-farm jobs, which was enough to keep pace with labour force growth, but not sufficient for more workers to move out of agriculture into more productive jobs.

Indeed, while the share of farm jobs fell from 62 per cent in 2000 to 53 per cent in 2010, the number of farm workers remained steady at about 240 million.

Also, India lags behind China in creation of higher value-added manufacturing and export-oriented jobs: 41 per cent of India's job creation in the past decade was in low-skill construction, compared with 16 per cent in China.

And, while India rivals China in tertiary education attainment, the share of people with secondary school education is only about one-third the ratio in China, which could lead to a shortage of medium-skill workers for expanding labour-intensive industries.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

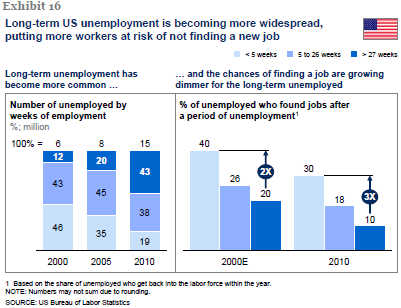

In the wake of the "Great Recession," the deteriorating position of low- and medium-skill workers has raised concerns about income inequality across advanced economies.

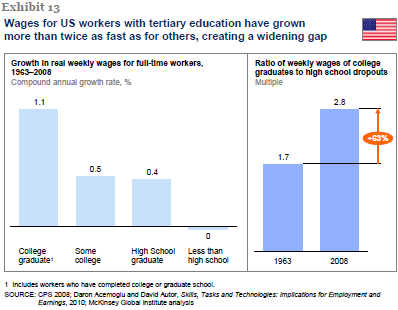

However, the growing polarisation of income that is so apparent today reflects a long decline in the role of low - and medium-skill labour (workers with just high school education or some post-secondary schooling at most).

Such workers were once essential to the growth of advanced economies. But since the late 1970s, companies have come to rely increasingly on investments in labour-saving machinery and information technology to raise productivity.

They have also invested in R&D and knowledge workers to help drive innovation. As a result, demand for the kinds of workers who make up three-quarters of the labour force has fallen - and, along with it, the share of national income that goes to workers.

After rising steadily from 1950 to 1975, labour's share of income in advanced economies fell from the 1980s onward, and now stands below the 1950 level.

High-skill workers (those with college degrees) remained in high demand and saw their wages rise - by about 1.1 per cent a year in real terms in the United States, while wages declined slightly in real terms for workers who did not complete high school.

Over 30 years, this has led to a widening gap between incomes of college-educated workers and workers with lower skills.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

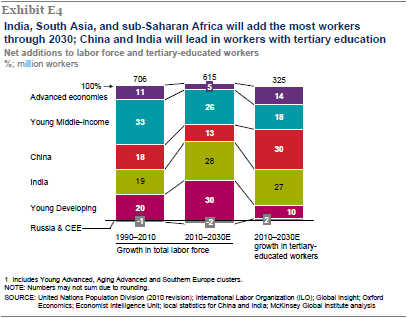

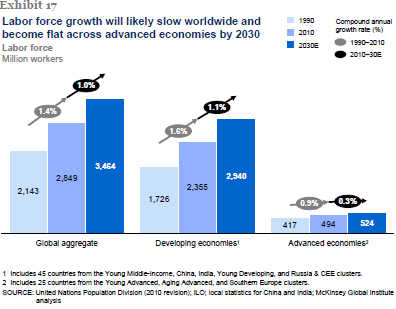

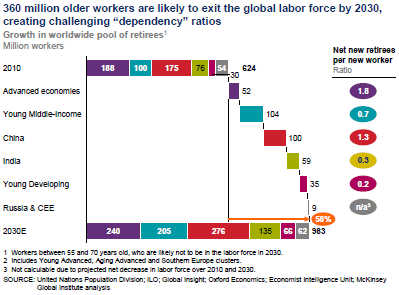

The most important trend shaping the global labor supply in the next two decades will be slower growth. New workers will enter at a slower rate, and older workers will leave in higher numbers.

The overall effect will be to reduce the annual growth rate of the global labour force from about 1.4 per cent annually between 1990 and 2010 to about one per cent to 2030.

China's labour force growth will likely drop by almost half, to just 0.5 per cent annually - in "Aging advanced" economies, labour forces will shrink and will likely be flat in Southern Europe.

Among the advanced economy clusters, only the "Young advanced" will grow its labour force, but only at about 0.6 per cent annually to 2030.

Over the next two decades, China will be replaced by India and the "Young developing" economies of South Asia and Africa as the leading source of new workers in the global market.

These nations will supply 60 per cent of the more than 600 million net new workers that we project will be added to the global labour supply, bringing the total global labor force to 3.5 billion in 2030.

While China will be eclipsed as the world's major source of low-cost labour, it will assume a new and potentially more important role as the largest supplier of college-educated workers to the global labor force.

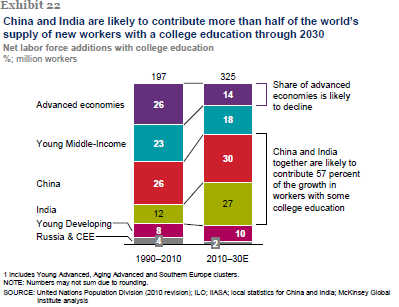

Between them, China and India will contribute 57 per cent of the world's new workers with some college education through 2030.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

With slow-growing or even shrinking labour forces - and lower laboir participation rates, also due to ageing - economies will need to accelerate productivity growth.

To maintain historical rates of GDP growth, we estimate that the "Aging advanced" economies would need to increase productivity growth by about 60 per cent of historical levels, to about 1.9 per cent annually.

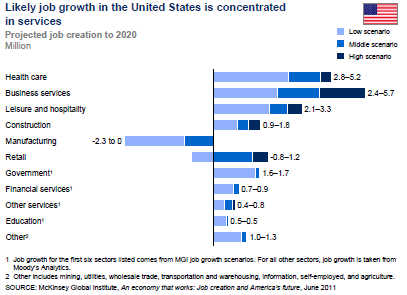

Advanced economies would still need to push hard for higher productivity improvements, which will require rapid expansion in highly knowledge-intensive sectors of the economy, such as advanced manufacturing, health care, and business services.

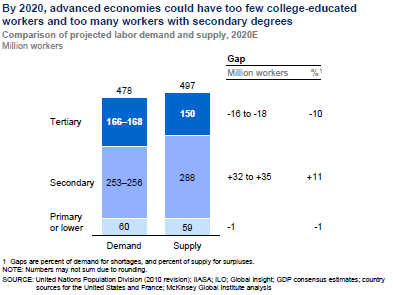

This, in turn, would depend on access to high-skill workers - which, at current growth rates of supply, may lag behind demand. We project that by 2020, advanced economies could have about 16 million to 18 million too few workers with tertiary degrees, or about 10 percent of their demand.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

In developing countries, if patterns of educational attainment and job creation do not change, the demographic advantages (young and rapidly growing populations) that have helped many of these nations prosper could become an economic and political burden.

Based on current population and education trends, India could have 27 million too many low-skill workers, who would likely be trapped in low-productivity, low-income work.

"Young developing" economies could have 31 million similarly positioned low-skill workers.

Meanwhile, India and "Young developing" economies could have 45 million too few workers with secondary school education.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

From rural schools in India to the top universities in advanced countries, technology can be used to extend the capacity of schools and teachers. Even now, teachers in parts of India are reaching low-income students through DVD-based lessons, and top US professors are giving classes to hundreds of thousands of students per semester, rather than hundreds, through online systems.

The need for innovation is high and will require more resources than governments alone can provide: private industry, private investors, and the social sector also will need to help.

Even with these steps, the shortages MGI projects would not disappear entirely. Both advanced and developing economies will also need to consider steps to raise demand for less-skilled workers.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

Developing economies can create demand for less educated workers by encouraging the expansion of labor-intensive sectors.

By moving up the value chain - from supplying raw food or raw materials and intermediates to processed food and finished goods - economies create more jobs.

By scaling up its garment manufacturing sector, Bangladesh, for example, created employment opportunities for millions of low-skill women, many of whom had never worked in the formal economy before.

Government can also help create jobs in the manufacturing and construction sectors by reducing the regulatory barriers that inhibit new enterprises and infrastructure development.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

Today, the effects of changes in labour demand and supply are most apparent in advanced economies, but they are also beginning to be felt in developing ones.

Across the global labour market there are growing mismatches between worker skills and employer needs (in France there are too few college graduates; in India, there aren't enough workers with secondary education).

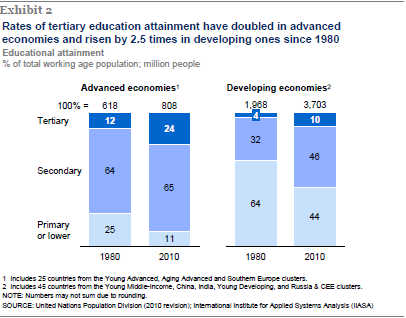

Average skill levels also rose rapidly. From 1980 to 2010, the number of college graduates in the world labour force rose by 245 million. The proportion of college graduates in the labour force doubled in advanced economies and grew by more than 2.5 times in developing economies.

Around the world, about 700 million high school graduates joined the labour force, raising the global proportion of workers with secondary education to 48 per cent in 2010.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

Developing economies have benefited from favourable demographic forces: large, and rapidly growing populations that can fill global demand for labour.

This supply of workers helped meet domestic needs, as nations industrialised and job creation shifted from low-productivity agricultural to manufacturing, construction, and services in growing urban centres.

These expanding labour forces also helped fill a global need for low-cost labour.

The rapid rise of China in the past three decades was made possible by the development of a modern industrial workforce.

From 1980 to 2010, China's non-farm labor force grew by 315 million to around 475 million, and now accounts for 60 per cent of the total labour force.

The result of labour force expansion and the shift to non-farm work was a rapid rise in productivity and per capita GDP.

From 1990 to 2010, China's productivity growth averaged 9.8 per cent per year, about one-fifth of which was driven by workers moving into non-farm employment - a powerful driver of productivity because non-farm workers were seven times as productive as farm workers.

In 1980, China's GDP per capita was less than three per cent of the average for advanced economies; by 2010, it had risen to 20 per cent.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

The Indian labour force grew from about 260 million in 1980 to 470 million in 2010, and India created millions of non-farm jobs - but not on the scale that China achieved.

From 2000 to 2010, India added 67 million non-farm jobs, just enough to keep pace with the growth of its labour force.

Relatively few of these jobs (about 19 per cent) were associated with exports: 41 per cent were in the construction sector, compared with 16 per cent in China. Just 12 per cent of India's non-farm job growth came from manufacturing, compared with 29 per cent in China. India also has lagged behind China in raising the skills of its workforce.

While it has comparable numbers of workers with a tertiary education, the share of people with secondary education in India is less than half the ratio in China and many other developing economies.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

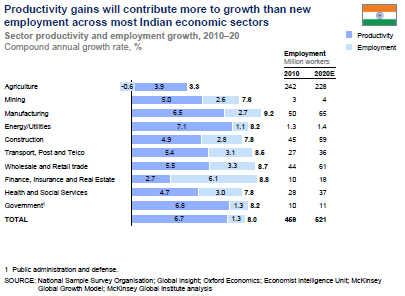

The results of the slower evolution in India's labour force are reflected in its growth and productivity record. India's productivity growth rate was about half of China's during the 1990-2010 period.

This was partly due to the slower transition out of agriculture, which accounted for only about a tenth of India's productivity improvement and about a fourth of the impact China got from that shift.

By 2010, Indian per capita GDP had more than tripled from the 1980 level, rising from 4.3 per cent of advanced economy levels to 9 per cent.

However, the gap between India's per capita GDP and that of advanced economies is now greater than China's.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

In the past 20 years, the drive for global competitiveness has shaped job creation across advanced economies.

Companies based in wealthy nations adopted technology, streamlined business processes, and took advantage of new sources of low-cost labour - often as they expanded their global footprints.

As a result, productivity growth in advanced economies averaged 1 to 2 percent annually.

During this time, employment in services (both low- and high-skill) grew rapidly, while employment in manufacturing, mining, and agriculture sectors fell (even in countries that are strong exporters of manufactured goods).

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

Increasing use of technology and the drive for productivity have all raised demand for high-skill workers, while depressing job growth for workers with lower skills.

Production and simple transaction jobs (e.g., assembly line work or answering a customer service call) have been automated or, in some cases, shipped to lower-cost locations.

At the same time, jobs have grown quickly in "interaction" work, which requires face-to-face contact. These jobs include many low-skill jobs (e.g., home health aides), as well as professions, such as law and medicine.

In the United States, the number of interaction jobs grew by 8.9 million from 2002 to 2010; about half of those jobs required tertiary education.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

In the coming decades, the dynamics driving the global labour market will evolve. The most significant change will be slower growth of labour forces around the world.

The sharpest declines are likely in the ageing economies - which now will include China. As China's labour force growth slows - by about half - India and the "Young developing" economies of South Asia and Africa will become the biggest sources of labour force growth in the coming decades.

But China, along with India, will likely be the world's largest source of college-trained workers.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

The first effect of ageing and slower labour force growth will be a heightened need to raise productivity to sustain GDP growth.

China, with its demographic dividend falling and incomes rising, would need to keep climbing the industrial value chain and accelerate productivity growth.

As a result, its labour needs will more closely mirror those of advanced economies, with a similar emphasis on high-skill work.

The demand for skilled workers will continue to grow far faster than supply, and the competition for talent will intensify and become increasingly global.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

MGI projects that the growth rate of the global labour force will fall by nearly a third, from 1.4 per cent annually in the 1990-2010 period to 1.0 per cent through 2030.

That would create 615 million net new additions to the global labour force, bringing the total number of workers to 3.5 billion in 2030, up from 2.9 billion in 2010.

Growth would decelerate during the two decades. In the 2010-20 decade, MGI projects 331 million net additions (down from 368 million in the 2000-10 period), dropping to 284 million net additions in the second decade, when ageing will place an even greater drag on global labour force growth.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

In China, labour force growth is likely to slow by half, from the current 0.9 per cent a year to about 0.5 per cent through 2030.

The Chinese labour force will reach 861 million in 2030, with a net increase of about 79 million, compared with its growth of 126 million from 1990 to 2010.

Growth will likely decelerate sharply in the decade from 2020 to 2030: to just 21 million from 58 million in the 2010-20 period, reflecting the effects of ageing and declining birth rates.

China is also likely to see a decline in its overall labour force participation rate due to ageing. At 70 per cent, China had among the world's highest participation rates in 2010.

MGI projects that figure will drop marginally to 67 per cent by 2030, when the number of Chinese aged 55 years and older will likely reach 43 per cent of the population - up from 26 per cent now.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

With the number of workers entering labour markets slowing in advanced economies and in the next 20 years China, India, and nations in the "Young developing" cluster will become the biggest contributors to the global labour pool.

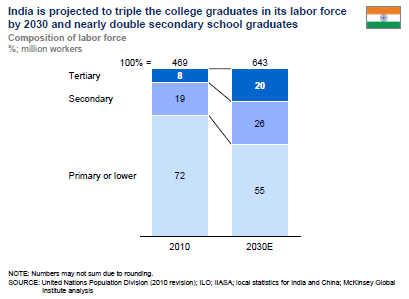

India's total labour force will continue to grow relatively quickly - at about 1.5 per cent annually - with about 174 million net additions by 2030. MGI projects the total labour force will reach 550 million by 2020 and 640 million in 2030.

During this period, India's working-age population is projected to grow about 1.5 per cent annually, while its population will also begin to age - but far less dramatically than in China or in advanced economies.

Overall, the number of Indians who fall into the prime working-age group (25 to 54 years) will hold steady at about 69 per cent of the population.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

India's relatively low labour force participation rate of 56 per cent is not expected to rise significantly. More young Indians will stay in school, reflecting the trend toward rising educational attainment.

Furthermore, India's low female labour participation rate (about 38 per cent today) is not likely to rise, because a growing number of households are expected to move out of subsistence, allowing more low-skill women to opt out of the labour force.

High-skill women, on the other hand, will see rising participation rates, but their numbers will remain small compared to those of their low-skill counterparts.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

The "Young developing" economies of South Asia and Africa (such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Kenya) will have the fastest-growing labour forces, growing at about 2.3 per cent annually.

That will add 187 million workers to the global labour market in the next two decades. Together with India, these nations will contribute about 360 million of the net new workers in the global labour force in the next 20 years, or about 60 per cent of the growth.

China's contribution to net labour force growth will decline from 18 per cent of the total to 10 per cent.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

While China will be eclipsed as the world's leading source of low-cost labour, it will assume a new and potentially more important role as the largest supplier of college-educated workers to the global labour force.

China's demographic dividend will likely be replaced by a "skill dividend," as the number of workers with college education in the labour force is projected to rise by 96 million in the next two decades, up from 52 million net additions of graduates in the last two decades.

This would raise the proportion of young workers with tertiary education to 33 per cent - about the projected average for advanced economies.

Click NEXT to read more...

World at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 bn people

At its current rate of growth in college completion, India would be close behind. India is on track to raise the number of college-educated workers in its labour force by 88 million in the next two decades, up from 24 million added in the last

two.

Between them, China and India are on track to raise the world supply of college educated workers by 184 million, and 57 per cent of all additional workers with some college education in 2030 are likely to come from those two nations.

India and China will also be dominant suppliers of graduates; based on current trends they will provide two-thirds of the increase in science and engineering graduates globally through 2030.