'Is India going to miss some more of its potential demographic dividend?'

'If so, it would be for two reasons: The demographic dividend can be fully exploited only if the people in the working age are actually working.'

'And second, if those working have proper education and skills, making them productive in the workplace.'

'On both counts, the country has fallen short,' points out T N Ninan.

Every country in the course of its development sees drops in its birth and death rates.

Since the two drops take place at different speeds and the death rate falls before the birth rate, the transition period is marked by high population growth before things stabilise.

The transition also sees a change in the age-wise population mix: The percentage of people in the working age (usually taken at 15 to 65 years) begins to rise, peaks and then falls.

If a greater percentage of the total population is working, it gives the economy a boost in its income, savings and productivity, and brings with it other benefits.

Countries that use the transition period successfully therefore enjoy an economic boom.

Between a quarter and 40 per cent of the rapid growth that the countries of East Asia enjoyed in the second half of the last century has been attributed to what has come to be called the demographic dividend.

The demographic transition is measured with the dependency ratio, ie those outside the working age (young and old) as a percentage of those in the working age.

India's ratio in 1980 was more or less the same as in 1960, at about 75 per cent.

This period was marked by the low, so-called Hindu rate of growth.

The ratio or percentage began dropping after that, just as the economic growth rate picked up.

The fall in the dependency ratio accelerated from the mid-1990s, from roughly 70 per cent to 60 per cent in a decade, and to a little above 50 per cent in the subsequent decade.

It is unlikely to be a pure coincidence that these have been the years of India's fastest economic growth.

Some projections suggest that the country's dependency ratio will flatten for the next two decades before it starts going up.

Such a trajectory would be different from those of some of the countries in East Asia, including China, which managed to reduce their dependency ratio to 40 per cent or less before reversing gear.

India is unlikely to manage that because its birth rate did not fall fast enough -- a failure of its health and nutrition policy.

That may well come in the way of the country achieving the sustained growth rates of between 8 per cent and 10 per cent that some East Asians achieved.

The question has to be asked: Is India going to miss some more of its potential demographic dividend? If so, it would be for two reasons: The demographic dividend can be fully exploited only if the people in the working age are actually working.

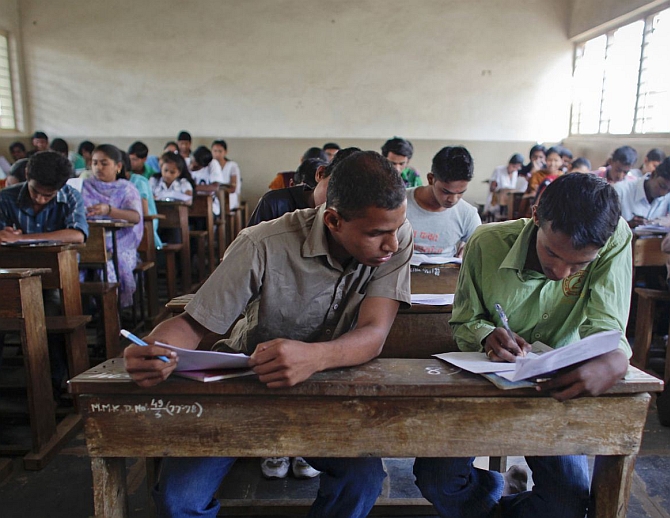

And second, if those working have proper education and skills, making them productive in the workplace.

On both counts, as everyone knows, the country has fallen short.

An employment survey recently released by the government says that only half those in the working age are actually working; that figure used to be 64 per cent in 2004-2005.

As for education and skills, the education surveys by Pratham and the patchy progress of the skills programme tell their unhappy stories.

Nevertheless, if India's dependency ratio remains in the low to 50 per cent range for the coming two decades before starting to climb, the window of opportunity is still open to make up for egregious failures on the health, education and employment fronts, and to reap what remains of the demographic dividend.

The problem is that the southern states, West Bengal and one or two others -- ahead of the northern states on the demographic transition -- have already seen the window of opportunity close, or will see it close in the next five years.

The window will remain open for another decade or so for a bunch of other states, while laggards like Bihar will continue to experience the demographic transition for much longer.

These last happen to be the states where the health and education attainments are the poorest, so how much of a dividend awaits them is an open question.

Remember that the demographic dividend is available only once in a country's time trajectory, because the population transition occurs only once.

Time is a luxury the country does not have.